Beyond the Ingot: Maximizing Secondary Aluminum Alloy Quality in Thin-Walled Automotive Castings

This technical summary is based on the academic paper "Quality of automotive sand casting with different wall thickness from progressive secondary alloy" by Lucia Pastierovičová, Lenka Kuchariková, Eva Tillová, Mária Chalupová, and Richard Pastirčák, published in PRODUCTION ENGINEERING ARCHIVES (2022). It has been analyzed and summarized for technical experts by CASTMAN.

Keywords

- Primary Keyword: Secondary Aluminum Alloy

- Secondary Keywords: Thin-Walled Casting, AlSi6Cu4 Alloy, Automotive Casting Quality, Brinell Hardness, Microstructure Analysis

Executive Summary

- The Challenge: The automotive industry's push for lightweighting and sustainability demands high-performance, thin-walled components made from recycled materials, yet impurities in these alloys can compromise mechanical properties.

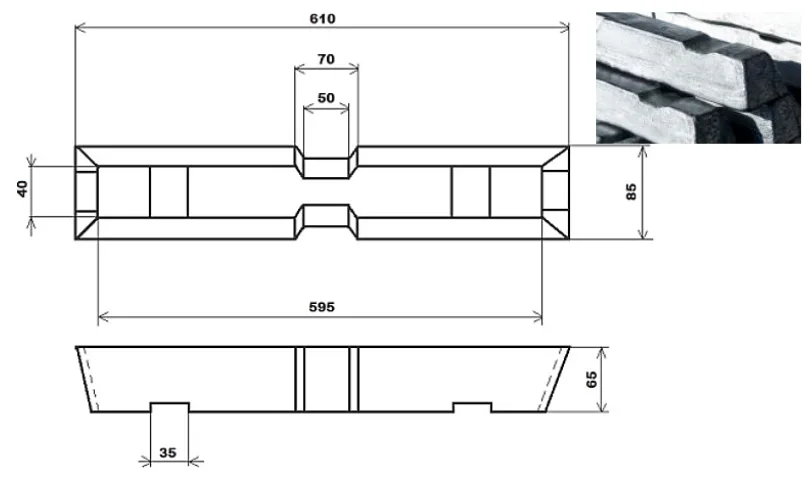

- The Method: Researchers performed gravity casting of a secondary AlSi6Cu4 alloy into a metal step-mold with varying wall thicknesses (2 mm to 15 mm) to analyze the resulting microstructure and mechanical hardness.

- The Key Breakthrough: Decreasing the casting wall thickness significantly refines the microstructure, leading to a quantifiable increase in Brinell hardness, effectively turning a design feature into a performance advantage.

- The Bottom Line: Utilizing metal molds for casting thin-walled components from secondary aluminum alloy is a highly effective strategy to enhance mechanical properties, mitigate the negative effects of impurities like iron, and produce lightweight, high-quality parts for the automotive industry.

The Challenge: Why This Research Matters for HPDC Professionals

In the relentless pursuit of fuel efficiency and sustainability, automotive engineers face a dual challenge: reducing component weight and increasing the use of recycled materials. Thin-walled aluminum castings are central to achieving the first goal, while using secondary aluminum alloy addresses the second. However, these objectives often conflict.

Secondary alloys, derived from scrap, save up to 95% of the energy required for primary aluminum production but often contain higher levels of impurities, particularly iron (Fe). Even in small amounts, iron can form brittle, needle-like intermetallic phases (such as β-Al₅FeSi) during solidification. These phases act as stress concentrators, degrading crucial mechanical properties like ductility and fatigue strength.

Simultaneously, casting thin-walled structures presents its own difficulties, including mold filling, feeding, and the risk of defects like microporosity due to rapid solidification. This research was necessary to investigate if the process conditions inherent in producing thin-walled castings could be leveraged to not only create lightweight parts but also to control and improve the microstructure of a higher-iron secondary alloy, turning a potential liability into a high-performance asset.

The Approach: Unpacking the Methodology

To isolate the effect of cooling rate on material quality, the research team employed a controlled and systematic approach.

- Material: The study used a hypoeutectic secondary AlSi6Cu4 alloy, a workhorse material in automotive applications, supplied by Confal Ltd. The alloy had a notable iron content of 0.449 wt.%.

- Casting Process: Ingots were melted in an electric resistance furnace and refined. The molten metal, at a temperature of 720 ± 5°C, was gravity cast into a standardized metal mold. This mold was designed to produce a single "step-casting" featuring a range of distinct wall thicknesses: 2 mm, 3 mm, 5 mm, 6 mm, 8 mm, and 15 mm. The use of a metal mold (as opposed to sand) ensures a much higher rate of heat extraction and solidification.

- Analysis Techniques:

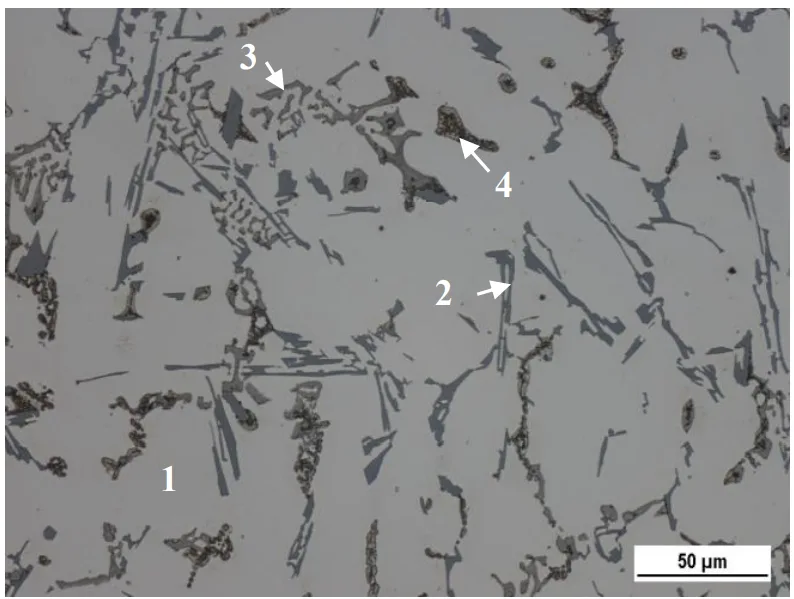

- Quantitative Metallography: Samples from the center of each step were prepared and etched. An image analyzer (NIS Elements) was used to numerically evaluate key structural parameters, including the average distance between dendritic arms of the α-phase, and the average area of eutectic Si particles and intermetallic phases.

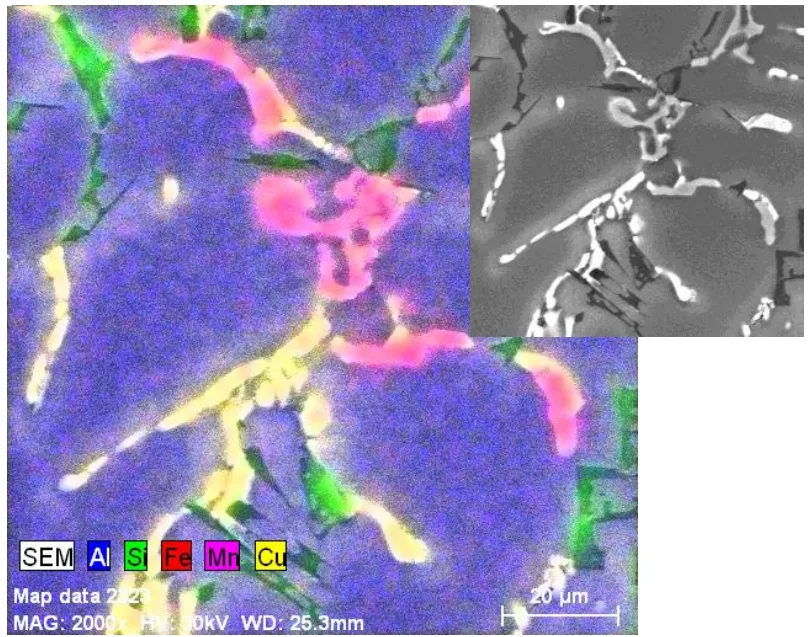

- Microstructural Identification: A Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) coupled with Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) analysis was used to precisely identify the morphology and chemical composition of the different phases within the microstructure.

- Mechanical Testing: The Brinell hardness (HBW) was measured on each wall thickness according to the STN EN ISO 6506-1 standard to quantify the changes in mechanical properties.

The Breakthrough: Key Findings & Data

The study delivered clear, data-driven evidence that wall thickness is a dominant factor in determining the final quality of castings made from this secondary alloy.

Finding 1: Wall Thickness Directly Dictates Microstructure Refinement

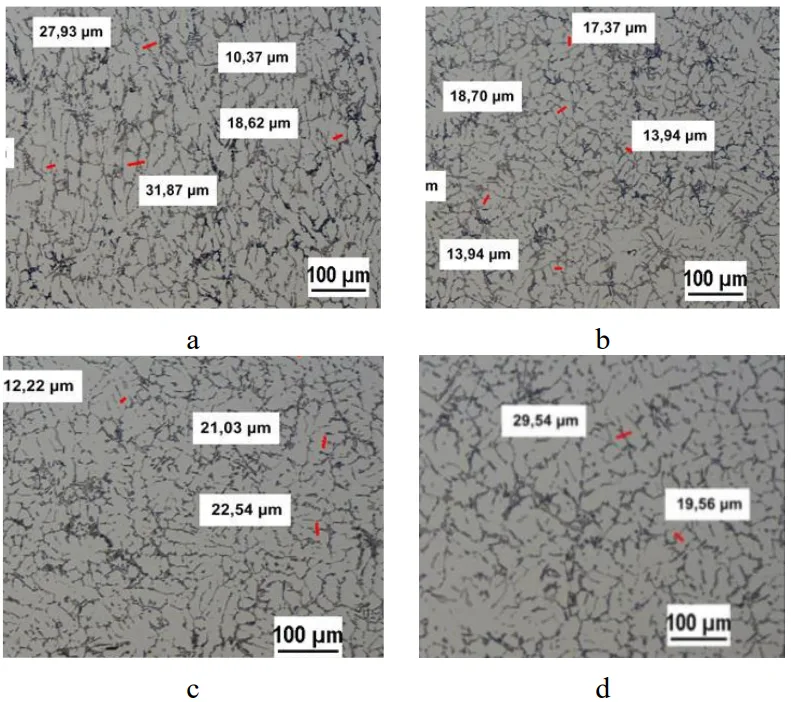

The rapid cooling experienced by the thinner sections of the casting had a profound refining effect on all major structural components.

- α-Phase Dendrites: The primary aluminum matrix structure became significantly finer in thinner walls. As shown in Figure 7, the average distance between dendritic arms increased from 16.51 µm in the 2 mm section to 27.15 µm in the 15 mm section.

- Eutectic Silicon: The size of the eutectic Si particles, which influences fracture behavior, was also heavily dependent on cooling rate. The average area of these particles in the 2 mm section was 41 µm², which grew dramatically to over 112 µm² in the 8 mm section (Figure 9).

- Overall Refinement: The paper's conclusion quantifies this effect, stating that the α-phase is approximately 27% smaller and the eutectic Si is 85% smaller in the thinnest wall compared to the thickest wall. This demonstrates a powerful correlation between section thickness and structural fineness.

Finding 2: Finer Microstructure Translates to Superior Hardness

The observed microstructural refinement was not merely academic; it translated directly into improved mechanical properties.

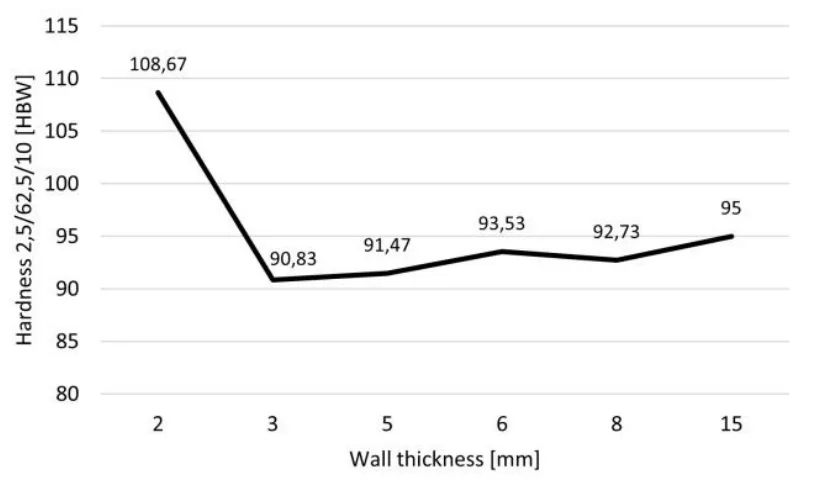

- Brinell Hardness: A clear inverse relationship was found between wall thickness and hardness. As detailed in Figure 13, the 2 mm section exhibited the highest average hardness of 108.67 HBW. This value steadily decreased as the wall thickened, reaching 92.73 HBW at the 15 mm section.

- Quantifiable Improvement: This represents a 12% increase in hardness in the thinnest section compared to the thickest. This improvement is attributed to the finer, more densely distributed strengthening phases (eutectic Si and Cu-rich phases) that result from rapid solidification in the thin walls.

Practical Implications for R&D and Operations

The findings of this study offer actionable insights for engineering and manufacturing teams working with aluminum castings.

- For Process Engineers: This study suggests that maximizing the cooling rate via mold design, mold material selection, and thermal management is a critical lever for improving the quality of parts made from secondary aluminum alloy. The data confirms that faster solidification helps refine the microstructure and boost mechanical properties.

- For Quality Control Teams: The data in Figure 13 illustrates the direct correlation between wall thickness and Brinell hardness. This relationship could inform new quality inspection criteria, where hardness measurements in specific sections can serve as a reliable, non-destructive proxy for confirming microstructural integrity and expected performance.

- For Design Engineers: The findings indicate that designing components with thinner walls (e.g., in the 2-5 mm range) can be an intentional strategy to enhance local mechanical properties. This allows for true lightweighting without compromising strength, as the design itself drives material performance improvements. Furthermore, the study shows that rapid cooling in metal molds can suppress the formation of the most harmful, needle-like iron phases, making secondary alloys more viable for demanding applications.

Paper Details

Quality of automotive sand casting with different wall thickness from progressive secondary alloy

1. Overview:

- Title: Quality of automotive sand casting with different wall thickness from progressive secondary alloy

- Author: Lucia Pastierovičová, Lenka Kuchariková, Eva Tillová, Mária Chalupová, Richard Pastirčák

- Year of publication: 2022

- Journal/academic society of publication: PRODUCTION ENGINEERING ARCHIVES

- Keywords: Quality of castings, Secondary aluminum alloy, Wall thickness, Quantitative analysis, Higher Fe content

2. Abstract:

This paperwork is focused on the quality of AlSi6Cu4 casting with different wall thicknesses cast into the metal mold. Investigated are structural changes (the morphology, size, and distribution of structural components). The quantitative analysis is used to numerically evaluate the size and area fraction of structural parameters (α-phase, eutectic Si, intermetallic phases) between delivered experimental material and cast with different wall thicknesses. Additionally, the Brinell hardness is performed to obtain the mechanical property benefits of the thin-walled alloys. This research leads to the conclusion, that the AlSi6Cu4 alloy from metal mold has finer structural components, especially in small wall thicknesses, and thus has better mechanical properties (Brinell hardness). These secondary Al-castings have a high potential for use in the automotive industry, due to the thin thicknesses and thus lightweight of the construction.

3. Introduction:

Aluminum cast alloys are a widely used material in the engineering industry, mainly due to their excellent combination of mechanical, tribological, and corrosion resistance properties. The dominant type in the production of automotive castings is Al-Si-Cu alloy. Recycling of aluminum scrap is characterized by a great benefit in electricity consumption, saving up to 95% of the electricity needed to produce primary alloys. However, recycling can lead to contamination with impurities like iron, which degrades mechanical properties by forming brittle intermetallic phases. Additionally, the usage of structural castings with thinner walls is required for lightweighting components, but these present challenges in casting. This research focuses on making wrought aluminum alloys using scrap aluminum recycling technologies to study the quality of thin-walled castings made from secondary AlSi9Cu4 alloy with higher Fe content cast into a metal mold.

4. Summary of the study:

Background of the research topic:

Al-Si-Cu alloys are essential for automotive castings due to their strength, fluidity, and heat resistance. The industry is increasingly focused on sustainability through recycling (creating secondary alloys) and lightweighting through thin-walled designs.

Status of previous research:

Previous research has established that iron impurities in secondary aluminum alloys are detrimental to mechanical properties. It is also known that casting into metal molds leads to faster solidification and finer dendritic structures compared to sand molds. However, the specific interaction between wall thickness, the microstructure of a secondary alloy with higher iron, and the resulting mechanical properties in a metal mold casting required further investigation.

Purpose of the study:

The aim of this work is to study the quality of thin-walled castings made from a secondary AlSi6Cu4 alloy with higher Fe content. The study investigates the effect of different wall thicknesses on the structural changes (morphology, size, distribution of phases) and the resulting Brinell hardness when cast into a metal mold.

Core study:

The core of the study is a quantitative comparison of the microstructure and hardness across different sections of a step-casting made from a secondary AlSi6Cu4 alloy. By varying the wall thickness from 2 mm to 15 mm, the study directly correlates the cooling rate with the size of the α-phase dendrites, eutectic silicon, intermetallic phases, and the final Brinell hardness of the material.

5. Research Methodology

Research Design:

The study used an experimental design where a single secondary AlSi6Cu4 alloy was cast into a standardized metal step-mold. The independent variable was the wall thickness of the casting (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 15 mm), which directly influences the cooling rate. The dependent variables were the microstructural parameters (dendritic arm spacing, phase area) and the mechanical hardness (Brinell).

Data Collection and Analysis Methods:

Samples were taken from each thickness step for analysis. Data was collected using optical microscopy with an image analyzer for quantitative measurements, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with EDX for phase identification, and a standard Brinell hardness tester. A minimum of 40 measurements were averaged for the quantitative analysis results.

Research Topics and Scope:

The research scope was limited to the as-cast condition of a specific secondary hypoeutectic AlSi6Cu4 alloy. The investigation focused on the influence of wall thickness on microstructure and Brinell hardness when gravity cast into a metal mold. It did not investigate other casting methods (e.g., HPDC) or the effect of subsequent heat treatments.

6. Key Results:

Key Results:

- Increasing wall thickness leads to a coarser microstructure. The average dendritic distance of the α-phase increased from 16.51 µm (at 2 mm) to 27.15 µm (at 15 mm).

- The size of eutectic Si particles increased significantly with wall thickness, from an average area of 41 µm² (at 2 mm) to over 100 µm² (at 15 mm).

- Despite the higher iron content, the fast cooling rate of the metal mold suppressed the formation of detrimental needle-like β-Al₅FeSi phases, favoring a less harmful skeleton-like Al₁₅(FeMn)₃Si₂ morphology.

- Brinell hardness is inversely proportional to wall thickness. The highest hardness (108.67 HBW) was measured in the thinnest (2 mm) section, while the lowest (92.73 HBW) was in the thickest (15 mm) section. This represents a 12% improvement in hardness in the thinnest section.

Figure Name List:

- Fig. 1. Supplied experimental material in form of ingots

- Fig. 2. AlSi6Cu4 step-casting from the metal mold

- Fig. 3. Microstructure of delivered ingots from AlSi6Cu4, etch. Dix-Keller.

- Fig. 4. EDX analysis of structural components in delivered ingots of AlSi6Cu4 cast alloy, etch. Dix-Keller.

- Fig. 5. The microstructure changes in step-casting, etch. Dix-Keller

- Fig. 6. Quantitative analysis of α-phase in step-casting, etch. Dix Keller

- Fig. 7. Results of the average distance of α-phase considering wall thickness from NIS Elements

- Fig. 8. Quantitative analysis of eutectic Si in step-casting, etch. Dix-Keller

- Fig. 9. Results of the average area of eutectic Si considering wall thickness from NIS Elements

- Fig. 10. Results of the average area of intermetallic phases considering wall thickness from NIS Elements

- Fig. 11. Quantitative analysis of Cu-rich phases in step-casting, etch. 0.5% HF

- Fig. 12. Quantitative analysis of eutectic Si in step-casting, etch. Dix-Keller.

- Fig. 13. Average Brinell hardness values for AlSi6Cu4 casting with different wall thickness

1 – α-phase; 2 – eutectic Si; 3 – Fe-rich phase; 4 – Cu-rich phase

7. Conclusion:

The study concludes that casting a secondary AlSi6Cu4 alloy into a metal mold results in a finer structure and superior structural components, particularly in thinner wall sections. This refined microstructure leads directly to better Brinell hardness. These findings demonstrate that secondary aluminum castings have high potential for use in the automotive industry for producing lightweight, thin-walled constructions. The increasing wall thickness affects the hardness and size of the structural components: the α-phase is about 27% smaller and eutectic Si is about 85% smaller in the thinnest wall versus the roughest. Brinell hardness is about 12% higher in the thinnest thickness and decreases with increasing wall thickness.

8. References:

- Bacaicoa, I., Luetje, M., Zeismann, F., Geisert, A., Fehlbier, M., Brueckner-Foit, A., 2019. On the role of Fe-content on the damage behavior of an Al-Si-Cu alloy. Procedia Structural Integrity, 23, 33-38, DOI: 10.1016/j.prostr.2020.01.059

- Cais, J., 2015. Electron microscopy. Metalografie, Centrum pro studium vysokého školství, Praha. (in Czech)

- Castro-Sastre, M.Á., García-Cabezón, C., Fernández-Abia, A.I., Martín-Pedrosa, F., Barreiro, J., 2021. Comparative Study on Microstructure and Corrosion Resistance of Al-Si Alloy Cast from Sand Mold and Binder Jetting Mold. Metals, 11(9), 1421, DOI: 10.3390/met11091421

- Davor, S., Špada, V., Iljkić, D., 2019. Influence of natural aging on the mechanical properties of high pressure die casting (HPDC) EN AC 46000-AlSi9Cu3(Fe) Al alloy. Materials Testing 61(5), 448-454, DOI: 10.3139/120.111341

- Fiocchi, J., Biffi, C.A., Tuissi, A., 2020. Selective laser melting of high-strength primary AlSi9Cu3 alloy: Processability, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Materials & Design, 191, 108581, DOI: 10.1016/j.matdes.2020.108581

- Ji, S., Yang, W., Gao, F., Watson, D., Fan, Z., 2013. Effect of iron on the microstructure and mechanical property of Al-Mg-Si-Mn and Al-Mg-Si diecast alloys. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 564, 130-139, DOI: 10.1016/j.msea.2012.11.095

- Kasala, J., Pernis, R., Pernis, I., Ličková, M., 2011. Influence of iron and mangan quality on porn level in the Al-si-Cu, Chem. Letters, 105, 627-629. (in Slovak)

- Kasińska, J., Bolibruchová, D., Matejka, M., 2020. The Influence of Remelting on the Properties of AlSi9Cu3 Alloy with Higher Iron Content. Materials (Basel), 13(3), 575, DOI: 10.3390/ma13030575

- Kaufman, J., Rooy, E., 2004. Aluminum alloy castings: properties, processes, and applications, ASM International, USA.

- Kuchariková, L., Liptáková, T., Tillová, E., Kajánek, D., Schmidová, E., 2018. Role of Chemical Composition in Corrosion of Aluminum Alloys. Metals, 8(8), 581, DOI: 10.3390/met8080581

- Kuchariková, L., Tillová, E., Pastirčák, R., Uhríčik, M., Medvecká, D., 2019. Effect of Wall Thickness on the Quality of Casts from Secondary Aluminium Alloy. Manufacturing Technology, 19(5), 797-801, DOI: 10.21062/ujep/374.2019/a/1213-2489/MT/19/5/797.

- Li, F., Zhang, J., Bian, F., Fu, Y., Xue, Y., Yin, F., Xie, Y., Xu, Y., Sun, B., 2015. Mechanism of Filling and Feeding of Thin-Walled Structures during Gravity Casting. Materials, 8(6), 3701-3713. DOI: 10.3390/ma8063701.

- Mahta, M., Emamy, M., Cao, M., Xinjin, J., Campbell, John., 2008. Overview of B-A15FeSi phase in Al-Si alloys. Materials Science Research Trends, 251-272.

- Mae, H., Teng, X., Bai, Y., Wierzbicki, T., 2008. Comparison of ductile fracture properties of aluminum castings: Sand mold vs. metal mold. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 45(5), 1430-1444, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2007.10.016.

- Qi, M., Li, J., Kang, Y., 2019. Correlation between segregation behavior and wall thickness in a rheological high pressure die-casting AC46000 aluminum alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 8(4), 3565-3579, DOI: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.03.016.

- Reyes, A.E.S., Guerrero, G.A., Ortiz, G.R., Gasga, J.R., Robledo, J.F.G., Flores, O.L., Costa, P.S., 2020. Microstructural, microscratch and nanohardness mechanical characterization of secondary commercial HPDC AlSi9Cu3-type alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 9, 4, 8266-8282, DOI: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.05.098.

- Roučka, J., 2004. Metalurgy of non-ferrous alloys, Cerm, Brno.(in Czech)

- Tillová, E., Chalupová, M., 2009. Structural analysis of Al-Si, EDIS, Žilina. (in Slovak)

Expert Q&A: Your Top Questions Answered

Q1: Why was a metal mold chosen for this experiment instead of a sand mold, which is also common in the automotive industry?

A1: The researchers specifically chose a metal mold to achieve the very high cooling rates necessary for producing sound, thin-walled castings. A metal mold extracts heat much faster than a sand mold. This allowed the study to isolate the effects of rapid solidification on the microstructure and properties of the secondary alloy, which is a key condition for modern lightweight component manufacturing.

Q2: The paper notes a higher iron (Fe) content of 0.449%, which is typically a concern. Why didn't the detrimental needle-like β-Al₅FeSi phase become a major issue in these castings?

A2: This is one of the most important takeaways from the research. The extremely rapid solidification imposed by the metal mold, especially in the thinner sections, suppressed the formation of the harmful needle-like β-phase. The EDX analysis in Figure 4 confirmed that the dominant Fe-rich phase was a less detrimental, skeleton-like Al₁₅(FeMn)₃Si₂ phase. This shows that process control (i.e., high cooling rate) can be used to mitigate the negative effects of certain impurities in secondary alloys.

Q3: Looking at Figure 9, the average area of eutectic Si increases sharply from 2 mm to 8 mm, but then seems to plateau or even slightly decrease at 15 mm. Why isn't the growth continuous?

A3: The paper does not explicitly explain this plateau. However, it is likely due to the complex solidification dynamics in thicker sections. While the cooling rate continues to decrease with thickness, the relationship is not linear. At thicknesses beyond 8 mm, the solidification front slows significantly, allowing more time for silicon modification and different growth patterns to emerge, which could lead to the observed plateau in the average particle area. The critical finding remains the dramatic difference between thin (<5 mm) and thick (>8 mm) sections.

Q4: How does the hardness of this secondary alloy cast in a metal mold compare to what might be expected from a sand casting?

A4: The paper references a 2019 study by Kuchariková which examined a similar secondary alloy cast in a sand mold. It notes that the structure of the casting from the metal mold is finer. While a direct hardness comparison isn't the focus, the measured hardness of 90.83 HBW at 3 mm in this study is nearly identical to the 90 HBW reported in the sand mold study at 3 mm. This suggests that using a metal mold can produce parts with comparable or better hardness due to the finer structure, making it a superior process for achieving high-quality components from recycled material.

Q5: What is the practical significance of the 12% increase in Brinell hardness observed in the 2 mm section compared to the 15 mm section?

A5: A 12% increase in hardness is a substantial improvement in mechanical properties. For automotive components subjected to wear, contact stress, or requiring high structural rigidity, this localized increase can be a significant design advantage. It means that by simply designing a feature to be thin, engineers can inherently boost its performance without changing the alloy or adding costly secondary processing steps. This directly links component design (wall thickness) to material performance.

Conclusion: Paving the Way for Higher Quality and Productivity

This research provides compelling evidence that the challenges of using secondary aluminum alloy in high-performance, lightweight applications can be overcome through intelligent process control. The study clearly demonstrates that for AlSi6Cu4 castings, thinner walls and the associated rapid cooling rates of a metal mold are not a liability but a powerful tool for refining microstructure and significantly enhancing mechanical hardness. By leveraging this principle, manufacturers can produce stronger, more reliable, and lighter components while advancing sustainability goals.

At CASTMAN, we are committed to applying the latest industry research to help our customers achieve higher productivity and quality. If the challenges discussed in this paper align with your operational goals, contact our engineering team to explore how these principles can be implemented in your components.

Copyright Information

- This content is a summary and analysis based on the paper "Quality of automotive sand casting with different wall thickness from progressive secondary alloy" by "Lucia Pastierovičová, Lenka Kuchariková, Eva Tillová, Mária Chalupová, Richard Pastirčák".

- Source: https://doi.org/10.30657/pea.2022.28.20

This material is for informational purposes only. Unauthorized commercial use is prohibited.

Copyright © 2025 CASTMAN. All rights reserved.