This technical summary is based on the academic paper "The Influence of Returnable Material on Internal Homogeneity of the High-Pressure Die-Cast AlSi9Cu3(Fe) Alloy" by Marek Matejka, Dana Bolibruchová, and Radka Podprocká, published in Metals (2021).

Keywords

- Primary Keyword: Returnable Material in HPDC

- Secondary Keywords: AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy, HPDC, microstructure, porosity, die-casting quality, recycled aluminum

Executive Summary

- The Challenge: High-pressure die casting operations must use returnable material (in-house scrap) to control costs and improve sustainability, but doing so risks introducing defects that compromise final casting quality.

- The Method: Researchers cast AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy using HPDC with systematically varied percentages of returnable material (10%, 55%, 75%, and 90%) and analyzed the resulting microstructure, porosity, and microhardness.

- The Key Breakthrough: Using up to 55% returnable material had a minimal negative impact on the alloy's internal structure; however, increasing the content to 75% and 90% caused significant coarsening of eutectic silicon particles, a key indicator of potential degradation in mechanical properties.

- The Bottom Line: For the widely used AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy, the optimal proportion of returnable material is approximately 50-55% to maintain casting integrity while maximizing economic and environmental benefits.

The Challenge: Why This Research Matters for HPDC Professionals

In the competitive world of high-pressure die casting, every decision impacts the bottom line. Reusing internal scrap—such as gating, risers, and noncompliant castings, collectively known as "returnable material"—is a standard practice to reduce raw material costs and minimize environmental impact. However, this economic advantage comes with a significant technical risk.

Each time material is remelted, it can introduce "hereditary properties" into the melt, including dissolved gases, oxides, and other impurities. As the proportion of this returnable material increases in the batch, so does the risk of defects like increased porosity and undesirable microstructural changes. This creates a critical dilemma for foundries: how much returnable material can be used before the quality of the final product is compromised? This study directly addresses this question for AlSi9Cu3(Fe), one of the most common alloys in the automotive industry, providing a data-driven framework for optimizing this crucial trade-off.

The Approach: Unpacking the Methodology

The research team conducted a rigorous, controlled experiment to isolate the effect of returnable material content on casting quality. Their methodology provides a clear and reliable basis for the findings.

Method 1: Alloy Preparation and Casting

- Alloy: The study used the subeutectic AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy (EN AC-46000), a workhorse material in the European automotive sector.

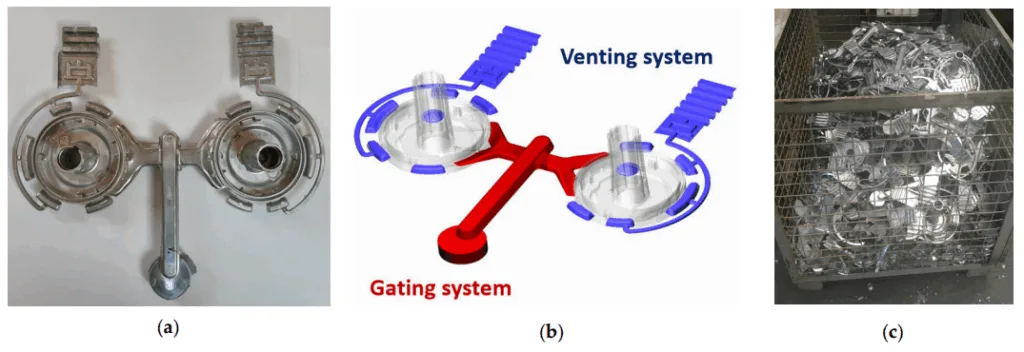

- Returnable Material: The recycled content consisted of noncompliant castings, gating systems, and parts of venting systems from previous production runs.

- Batches: Four experimental batches were prepared with increasing amounts of returnable material: 10% (Z10), 55% (Z55), 75% (Z75), and 90% (Z90).

- Casting Process: Castings were produced using a CLH 400 cold chamber HPDC machine under typical industrial parameters, including a melt temperature of 710 ± 10 °C and a maximum chamber pressure of 95 MPa.

Method 2: Material Analysis

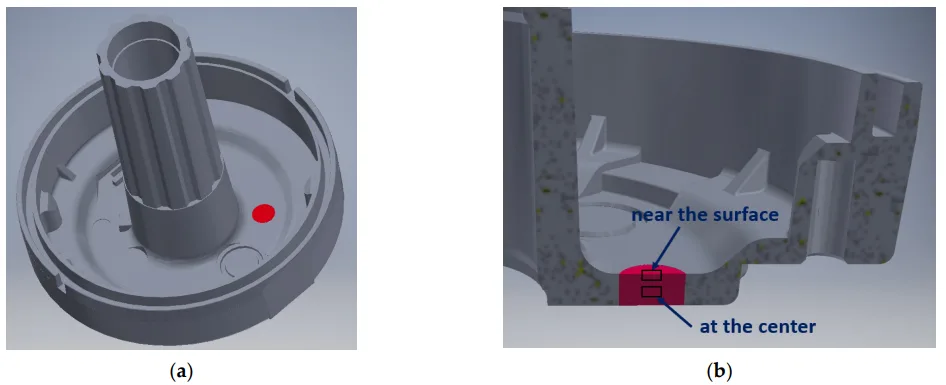

- Microstructure: Samples were taken from a 5 mm thick section of the casting and analyzed using optical microscopy (OM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to evaluate the size and shape of the eutectic silicon and other phases.

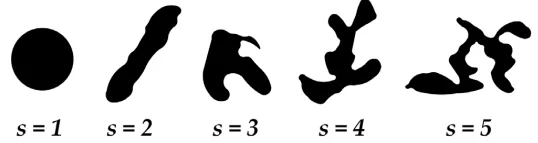

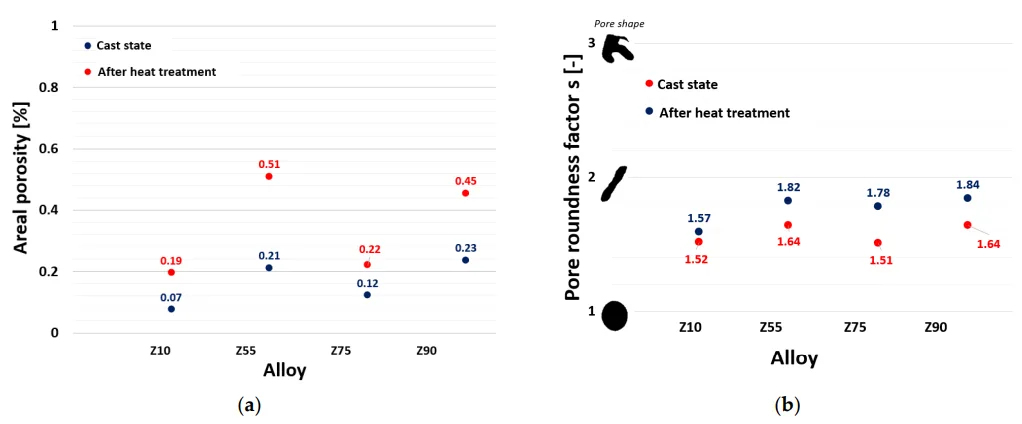

- Porosity: Two control cuts were made on each casting. The images were processed to determine the areal porosity (the percentage of the area covered by pores) and the pore roundness factor, a key metric for understanding the potential impact of pores on mechanical strength.

- Heat Treatment: A subset of castings was subjected to a heat treatment (370 ± 5 °C for 3 hours) to relieve internal stresses, and the effects on microstructure and porosity were also evaluated.

The Breakthrough: Key Findings & Data

The study revealed a clear threshold where the benefits of using returnable material are outweighed by the negative impact on the casting's internal structure.

Finding 1: Microstructure Degrades Significantly Above 55% Returnable Material

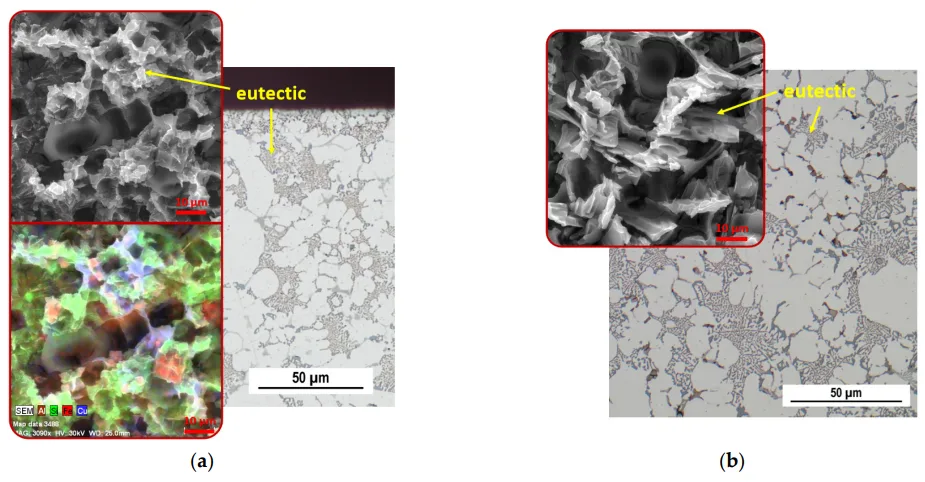

The morphology of the eutectic silicon (Si) is a critical factor in the mechanical performance of Al-Si alloys. The study found a distinct difference based on the percentage of returnable material.

- In the Z10 (10%) and Z55 (55%) alloys, the eutectic Si in the casting's central region exhibited a desirable plate-like morphology.

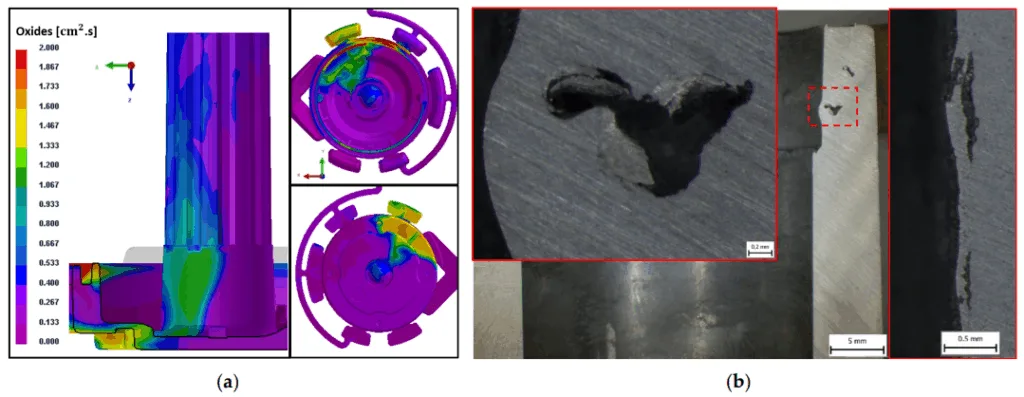

- However, as shown in the images from Figure 6 and Figure 7 of the paper, when the returnable material content increased to 75% (Z75) and 90% (Z90), the eutectic Si became coarsely irregular. This coarsening, particularly in the slower-cooling central regions, indicates a degradation of the microstructure that can lead to reduced strength and ductility.

Finding 2: Porosity Increases with High Scrap Content, Especially After Heat Treatment

While the overall porosity levels remained low (below 1%), the data showed a concerning trend at higher percentages of returnable material.

- In the as-cast state, the Z55 and Z90 alloys exhibited the highest areal porosity.

- As shown in Figure 13a, after heat treatment, porosity levels increased across all samples. The Z90 alloy showed the most dramatic increase, reaching an areal porosity of 0.81% in the A-A cut. This demonstrates that castings made with very high scrap content are more susceptible to pore growth during subsequent thermal processing, posing a quality risk.

Practical Implications for R&D and Operations

- For Process Engineers: This study suggests that exceeding a 55% returnable material content for AlSi9Cu3(Fe) may contribute to microstructure coarsening, particularly in casting sections prone to slower cooling (hot spots). Careful control of the batch composition is critical to ensure consistent quality.

- For Quality Control Teams: The data in Figure 13a of the paper illustrates that heat treatment can significantly increase areal porosity, especially in batches with high returnable material content. This finding could inform the development of more stringent quality inspection criteria for parts that undergo post-cast thermal processing.

- For Design Engineers: The findings confirm that pores and coarse microstructures tend to form in interdendritic spaces or hot spots. This reinforces the importance of using simulation and design-for-manufacturing principles to minimize hot spots, especially when the use of higher scrap ratios is anticipated.

Paper Details

The Influence of Returnable Material on Internal Homogeneity of the High-Pressure Die-Cast AlSi9Cu3(Fe) Alloy

1. Overview:

- Title: The Influence of Returnable Material on Internal Homogeneity of the High-Pressure Die-Cast AlSi9Cu3(Fe) Alloy

- Author: Marek Matejka, Dana Bolibruchová and Radka Podprocká

- Year of publication: 2021

- Journal/academic society of publication: Metals

- Keywords: aluminium alloy AlSi9Cu3; returnable material; HPDC; microstructure; porosity

2. Abstract:

Nowadays, high-pressure die-casting technology is an integral part of industrial production. High productivity, reduced machining requirements together with the low weight and advantageous properties of aluminium alloys form an ideal combination for the production of numerous components for various industries. The experimental part of the presented article focuses on the analysis of the change in the ratio of returnable material and commercial-purity alloy in a batch depending on the internal homogeneity of castings (microstructure, porosity and microhardness) from AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy. The use of returnable material in the batch is a key factor in achieving the maximum use of aluminium melt, which increases the economic efficiency of production and, last but not least, has a more favorable impact on the environment. Structural analysis showed that the increase in returnable material in the batch was visibly manifested in a change in the morphology of the eutectic Si. A negative change in the morphology of the eutectic Si particles was observed after increasing the returnable material content in the batch to 75%. The evaluation of porosity at control cuts showed the influence of the increase of returnable material in the batch, where the worst results were achieved by the alloy with 90% but also the one with 55% returnable material content in the batch.

3. Introduction:

The development of automobile production has driven a large increase in the demand for non-ferrous metal castings produced by high-pressure die casting (HPDC). The use of these castings reduces vehicle weight, thereby lowering fuel consumption and benefiting the environment. Concurrently, there is a growing demand to maximize the use of batch material by incorporating unused metal from the gating, riser, and venting systems (returnable material) into subsequent production. However, using returnable material can negatively impact final casting quality by introducing hereditary properties, increasing porosity, and adding undesirable elements to the melt. A key factor is determining the optimal amount of returnable material to maintain product quality while reducing input costs.

4. Summary of the study:

Background of the research topic:

The study is situated within the context of industrial HPDC of aluminium alloys, a cost-effective process for producing large quantities of dimensionally accurate parts. A major challenge in HPDC is managing porosity, which can arise from air entrapment during turbulent mold filling, dissolved hydrogen in the melt, shrinkage, and reoxidation. The AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy is widely used in this process, particularly in the automotive industry. The use of secondary (remelted) alloys, including in-house returnable material, is common practice for economic and environmental reasons, but it requires careful management to avoid compromising the mechanical properties of the final casting.

Status of previous research:

The paper references existing literature on the solidification characteristics of AlSi9Cu3 alloy, noting the formation of primary α-phase dendrites followed by eutectic crystallization. It acknowledges that porosity is a known major disadvantage of HPDC castings, with sources identified as air entrapment, dissolved gases, and shrinkage. Prior work also established that secondary alloys often have intentionally higher iron content to prevent die sticking but are not suitable for high-ductility applications. The literature confirms that the reuse of returnable material is economically necessary but introduces contaminants like oxides and hydrogen.

Purpose of the study:

The main aim of the study was to describe the effect of increasing the proportion of returnable material on the internal homogeneity (specifically porosity and microstructure) of HPDC castings made from AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy. The objective was to determine an optimal proportion of returnable material that could be used in the batch while maintaining the required quality of the castings.

Core study:

The core of the study was an experimental investigation where AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy was cast with four different ratios of returnable material: 10% (Z10), 55% (Z55), 75% (Z75), and 90% (Z90). The resulting castings were analyzed in both the as-cast state and after a stress-relief heat treatment. The analysis focused on changes in the microstructure (particularly the morphology of eutectic silicon), the microhardness of the primary α-phase, and the areal percentage and shape factor of porosity.

5. Research Methodology

Research Design:

The study employed a comparative experimental design. Four distinct alloy batches were created by varying a single independent variable: the percentage of returnable material. The dependent variables measured were microstructure characteristics, microhardness, and porosity metrics. The experiment was conducted under controlled, industrial-scale HPDC conditions to ensure the relevance of the findings.

Data Collection and Analysis Methods:

- Material Preparation: A subeutectic AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy (A226) was used. Returnable material, consisting of noncompliant castings, gating systems, and venting systems, was added to a primary melt to create batches with 10%, 55%, 75%, and 90% recycled content.

- Casting: A "Stator Buchse D 106/70" casting was produced in a double-cavity mold on a CLH 400 cold chamber die-casting press.

- Chemical Analysis: The chemical composition of each batch was determined by arc spark spectroscopy.

- Microstructural Analysis: Specimens were taken from a specified location (5 mm thickness) on the casting. They were prepared using standard metallographic techniques and evaluated using an NEOPHOT 32 optical microscope (OM) and a VEGA LMU II scanning electron microscope (SEM) for detailed morphology analysis.

- Microhardness Testing: Microhardness of the primary α-phase was measured using a Hanemann type Mod 32 device under a 10 p load, with the final value being an average of 20 measurements.

- Porosity Evaluation: Two control cuts (incisions) were made on each casting. The cuts were imaged with an AZ100 Multizoom Diascopic Microscope and analyzed using Quick PHOTO INDUSTRIAL software to quantify areal porosity and the pore roundness factor (s).

Research Topics and Scope:

The research was focused on the AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy produced via the HPDC process. The scope was limited to the investigation of internal homogeneity, specifically the influence of the returnable material ratio on:

1. Microstructure, with an emphasis on the morphology of eutectic silicon in both surface and central regions of the casting.

2. Microhardness of the primary α-phase.

3. Macroporosity, quantified by areal percentage and pore shape.

The study also included an analysis of these properties after a specific stress-relief heat treatment.

6. Key Results:

Key Results:

- Microstructure: An increase in returnable material content to 75% and 90% led to a visible coarsening of eutectic Si particles into an irregular morphology, particularly in the central region of the castings. The microstructure of the 55% alloy was nearly identical to the 10% alloy. The surface regions of all alloys maintained a finer, sharp-edged Si morphology due to higher cooling rates.

- Heat Treatment Effects: The applied heat treatment (370 °C for 3 h) resulted in the spheroidization and branching of the plate-like eutectic Si morphology in the central regions of all alloys, which is generally favorable for mechanical properties.

- Microhardness: The primary α-phase microhardness was consistently higher in the surface region compared to the central region. In the as-cast state, microhardness showed a slight increasing trend with higher returnable material content. After heat treatment, microhardness decreased for the Z55, Z75, and Z90 alloys compared to their as-cast state.

- Porosity: The areal porosity remained below 1% for all tested conditions. In the as-cast state, the Z90 and Z55 alloys showed the highest porosity values (up to 0.43%). After heat treatment, areal porosity increased in all castings, with the highest value of 0.81% measured in the Z90 alloy. The pore roundness factor remained in a narrow range (1.5 to 2.1), indicating that pores were predominantly spherical/oval, characteristic of gas porosity.

Figure Name List:

- Figure 1. Stator Buchse D 106/70 casting: (a) Double-cavity mould; (b) 3D model of the casting; (c) Returnable material.

- Figure 2. Place of sampling (red) of the casting for microstructure analysis: (a) Site within the casting; (b) Specimen regions evaluated.

- Figure 3. Numerical values of roundness factor “s” assigned to pore shapes.

- Figure 4. Images of the structure of the Z10 alloy casting in the cast state; OM, SEM: (a) surface region; (b) central region.

- Figure 5. Images of the structure of the Z55 alloy casting in the cast state; OM, SEM: (a) surface region; (b) central region.

- Figure 6. Images of the structure of the Z75 alloy casting in the cast state; OM, SEM: (a) surface region; (b) central region.

- Figure 7. Images of the structure of the Z90 alloy casting in the cast state; OM, SEM: (a) surface region; (b) central region.

- Figure 8. Images of the structure of the castings from the Z10 and Z55 alloys after heat treatment; OM, SEM: (a) Z10 surface; (b) Z10 central region; (c) Z55 surface; (d) Z55 central region.

- Figure 9. Images of the structure of the casting from the Z75 and Z90 alloys after heat treatment; OM, SEM: (a) Z75 surface; (b) Z75 central region; (c) Z90 surface; (d) Z90 central region.

- Figure 10. Dependence of the primary α-phase microhardness of AlSi9Cu3 alloy on the amount of returnable material in the batch and the measuring position on the specimen.

- Figure 11. Checking cuts (incisions) A-A and B-B of castings on the casting at position 1: (a) Location of cuts within the casting; (b) Location of cuts with respect to porosity in the casting.

- Figure 12. A-A cut through the casting shown in numerical simulation: (a) Display of hot spots; (b) Display of prediction of the presence of oxides and pores.

- Figure 13. Evaluation of porosity on the A-A cut (incision): (a) Areal porosity; (b) Pore roundness factor.

- Figure 14. Evaluation of porosity on the B-B cut: (a) Areal porosity; (b) Pore roundness factor.

- Figure 15. Porosity occurring near the casting walls: (a) Numerical simulation showing surface regions with increased presence of oxides; (b) Pores disrupting the geometry of the casting from Z55, after heat treatment.

7. Conclusion:

The study confirms the negative effect of a high proportion of returnable material in the batch on the microstructure of high-pressure die castings. As the content of returnable material increases, there is a negative change in the morphology of eutectic Si, specifically a coarsening of the particles, which is most pronounced in hot spots with lower cooling rates. The negative effect on porosity was less than anticipated, with areal porosity increasing only slightly. The applied heat treatment favorably refined the eutectic Si structure but, as expected, increased the areal porosity. Based on the results, it is concluded that a maximum of 50 to 55% of returnable material is suitable for batch dosing to produce castings where internal homogeneity and quality are critical. Larger proportions may be acceptable for components with less stringent structural requirements.

8. References:

- Bolibruchová, D.; Matejka, M.; Michalcová, A.; Kasińska, J. Study of natural and artificial aging on AlSi9Cu3 alloy at different ratios of returnable material in the batch. Materials 2020, 13, 4538, doi:10.3390/ma13204538.

- Bolibruchová, D.; Kuriš, M.; Matejka, M.; Gabryś, K.M.; Vicen, M. Effect of Ti on Selected Properties of AlSi7Mg0.3Cu0.5 Alloy with Constant Addition of Zr. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2021. 66, 65-72, doi:10.24425/amm.2021.134760.

- Eperješi, L.; Malik, J.; Eperješi, Š.; Fecko, D. Influence of returning material on porosity of die castings. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 13, 36-39, doi:10.21062/ujep/x.2013/a/1213-2489/MT/13/1/36.

- Ragan, E. Die Casting of Metals; Michal Vašek publishing house Prešov: Slovakia, 2007. (In Slovak)

- Podprocká, R.; Bolibruchová, D. Iron Intermetallic Phases in the Alloy Based on Al-Si-Mg by Applying Manganese. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2017, 17, doi:10.1515/afe-2017-0118.

- Hosford, F.W.; Caddell. M. R. Metal forming mechanics and metallurgy, third edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2007, 330, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511811111.

- Bolibruchova, D.; Richtarech, L.; Dobosz, S.M.; Major-Gabryś. Utilisation of mould temperature change in eliminating the Al5FeSi phases in secondary AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy. Archives of Metallurgy and Materials. 2017, 62. Doi: 10.1515/amm-2017-0051

- Adamane, A.R.; Fiorese, E.; Timelli, G.; Bonollo, F.; Arnberg, L. Influence of Injection Parameters on the Porosity and Tensile Properties of High-Pressure Die Cast Al-Si Alloys. A Rev. Int. J. Met. 2015, 9, 43-53, doi:10.1007/BF03355601.

- Hernandez-Ortega, J.J.; Zamora, R.; Palacios, J.; Lopez, J.; Faura, F. An Experimental and Numerical Study of Flow Patterns and Air Entrapment Phenomena During the Filling of a Vertical Die Cavity. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2010, 132, doi:10.1115/1.4002535.

- Pinto, H.; Silva, F.J.G. Optimisation of Die Casting Process in Zamak Alloys. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 517-525, doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2017.07.145.

- Cao, H.; Shen, Ch.; Wang, Ch.; Xu, H. Zhu. Direct Observation of Filling Process and Porosity Prediction in High Pressure Die Casting. Materials 2019, 12, 1099, doi:10.3390/ma12071099.

- Cao, L.; Liao, D.; Sun, F.; Chen, T.; Teng, Z.; Tang, Y. Prediction of gas entrapment defects during zinc alloy high-pressure die casting based on gas-liquid multiphase flow model. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, doi:10.1007/s00170-017-0926-5.

- Swillo, S.J.; Perzyk, M. Surface Casting Defects Inspection Using Vision System and Neural Network Techniques. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2013, 13, doi:10.2478/afe-2013-0091.

- Patel, J.M.; Pandya, Y.R.; Sharma, D.; Patel, R.C. Various Type of Defects on Pressure Die Casting for Aluminium Alloys. Ijsrd Int. J. Sci. Res. Dev. 2017, 5, 2321-0613.

- Bruna, M.; Remišová, A.; Sládek, A. Effect of Filter Thickness on Reoxidation and Mechanical Properties of Aluminium Alloy AlSi7Mg0.3. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2019, 64, 55-60, doi:10.24425/amm.2019.129500.

- Bonollo, F.; Gramegna, N.; Timelli, G. High-Pressure Die-Casting: Contradictions and Challenges. J. Miner. Met. Mater. Soc. 2015, 67, doi:10.1007/s11837-015-1333-8.

- Belov, N.A.; Aksenov, A.A.; Eskin, D.G. Iron in Aluminium Alloys, Alloying Element; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2002, doi:10.1201/9781482265019.

- Samuel, A.M.; Samuel, F.H.; Doty, H.W. Observations on the formation of β-A15FeSi in 319 type Al-Si alloys, J. Mater. Sci. 1996, 31, 5529-5539, doi:10.1007/BF01159327.

- Niklasa, A.; Bakedano, A.; Orden, S.; da Silva, M.; Noguésc, E.; Fernández-Calvo, A.I. Effect of microstructure and casting defects on the mechanical properties of secondary AlSi10MnMg(Fe) test parts manufactured by vacuum assisted high pressure die casting technology. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2, 4931–4938, doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2015.10.059.

- Vicen, M.; Fabian, P.; Tillová, E. Self-Hardening AlZn10Si8Mg Aluminium Alloy as an Alternative Replacement for AlSi7Mg0.3 Aluminium Alloy. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2017, 17, 139–142, doi:10.1515/afe-2017-0106.

- Chai, G., BÄckerud, L., RØlland, T. Dendrite coherency during equiaxed solidification in binary aluminum alloys, Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1995, 26, 965–970, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02649093.

- Žbontar, M.; Petrič, M.; Mrvar, P. The Influence of Cooling Rate on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of AlSi9Cu3. Metals 2021, 11, 186, doi:10.3390/met11020186.

- Timelli, G.; Bonollo, F. The influence of Cr content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of AlSi 9Cu 3(Fe) die-casting alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 528, 273–282, doi:10.1016/j.msea.2010.08.079.

- Timelli, G.; Bonollo, F. The Effects of Microstructure Heterogeneities and Casting Defects on the Mechanical Properties of High-Pressure Die-Cast AlSi9Cu3(Fe) Alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2014, 45, doi:10.1007/s11661-014-2515-7.

- Khan, S.; Elliott. R. Quench modification of aluminium-silicon eutectic alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Vol. 1996, 31, 3731-3737, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00352787.

- ASM Handbook, ASM International. Handbook Committee. Taylor Fr. 1998, 1521.

- Bolibruchová, D.; Pastirčák, R. Foundry Metallurgy of Non-Ferrous Metals; Publishers of University of Žilina EDIS Publishers Center of University of Žilina: Žilina, Slovakia, 2018. (in Slovak)

Expert Q&A: Your Top Questions Answered

Q1: Why was the AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy specifically chosen for this investigation?

A1: According to the paper, AlSi9Cu3(Fe) is the most widely used alloy in Europe for the HPDC process and is a dominant component in castings for the automotive industry. Its widespread industrial use makes understanding the effects of returnable material critical for a large number of manufacturers seeking to optimize their processes.

Q2: What exactly was included in the "returnable material" used in the experiments?

A2: The returnable material consisted of noncompliant castings, gating systems, and parts of the venting systems. This composition is representative of the typical in-house scrap that foundries remelt, ensuring the study's results are directly applicable to real-world production environments.

Q3: The paper mentions a heat treatment. What was its purpose and primary effect on the material?

A3: The heat treatment (heating to 370 °C for 3 hours) was chosen based on industrial requirements to reduce internal stresses in the casting. Its primary effect on the microstructure was favorable, causing the plate-like eutectic silicon to break up and become more rounded (spheroidization). However, it also had the negative effect of increasing the size of existing pores, leading to a higher measured areal porosity.

Q4: Did the chemical composition of the alloy change significantly as more returnable material was added?

A4: Based on Table 1 in the paper, the chemical composition remained relatively stable across the different batches. While there were minor fluctuations in elements like Si, Cu, and Mg, there were no drastic shifts that would suggest the returnable material was introducing significant contamination or causing major elemental loss. This indicates that the observed changes in microstructure were primarily due to the remelting process itself, not a major change in alloy chemistry.

Q5: What was the main type of porosity observed in the castings?

A5: The study concluded that porosity was caused primarily by the mechanism of bubble (air/gas pocket) formation. This was deduced from the pore shape analysis, where the roundness factor consistently fell in a narrow range indicative of spherical or oval shapes. This type of porosity is common in HPDC due to air entrapment during the high-velocity filling of the mold.

Q6: What is the final, practical recommendation on the maximum percentage of returnable material that should be used?

A6: The authors conclude that to maintain high quality and internal homogeneity, it is suitable to use a maximum of 50% to 55% returnable material in the batch for dosing. They note that larger proportions (over 55%) can be used, but are better suited for castings or components with static use or those that are not cyclically stressed, such as covers or cabinets.

Conclusion: Paving the Way for Higher Quality and Productivity

The challenge of balancing cost, sustainability, and quality is at the heart of modern manufacturing. This research provides a clear, data-backed guideline for one of the most common practices in high-pressure die casting: the use of in-house scrap. The key breakthrough is the identification of a 50-55% threshold for Returnable Material in HPDC of AlSi9Cu3(Fe) alloy, beyond which the risk to microstructural integrity significantly increases. By adhering to this guideline, foundries can confidently maximize economic efficiency without unknowingly compromising the quality and performance of their final products.

At CASTMAN, we are committed to applying the latest industry research to help our customers achieve higher productivity and quality. If the challenges discussed in this paper align with your operational goals, contact our engineering team to explore how these principles can be implemented in your components.

Copyright Information

This content is a summary and analysis based on the paper "The Influence of Returnable Material on Internal Homogeneity of the High-Pressure Die-Cast AlSi9Cu3(Fe) Alloy" by "Marek Matejka, Dana Bolibruchová and Radka Podprocká".

Source: https://doi.org/10.3390/met11071084

This material is for informational purposes only. Unauthorized commercial use is prohibited.

Copyright © 2025 CASTMAN. All rights reserved.