This article introduces the paper 'A cost-efficient process route for the mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings' published by 'RWTH Aachen University'.

1. Overview:

- Title: A cost-efficient process route for the mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings

- Author: Mohamed Youssef Ahmed Youssef

- Publication Year: 2021

- Publishing Journal/Academic Society: Ergebnisse aus Forschung und Entwicklung, Band 28 (2021) Gießerei-Institut der RWTH Aachen

- Keywords: High pressure die casting (HPDC), RheoMetalTM process, Thin-walled structural aluminum body castings, Cost calculation study, Mechanical properties, Rivetability, Crash resistance

2. Abstracts or Introduction

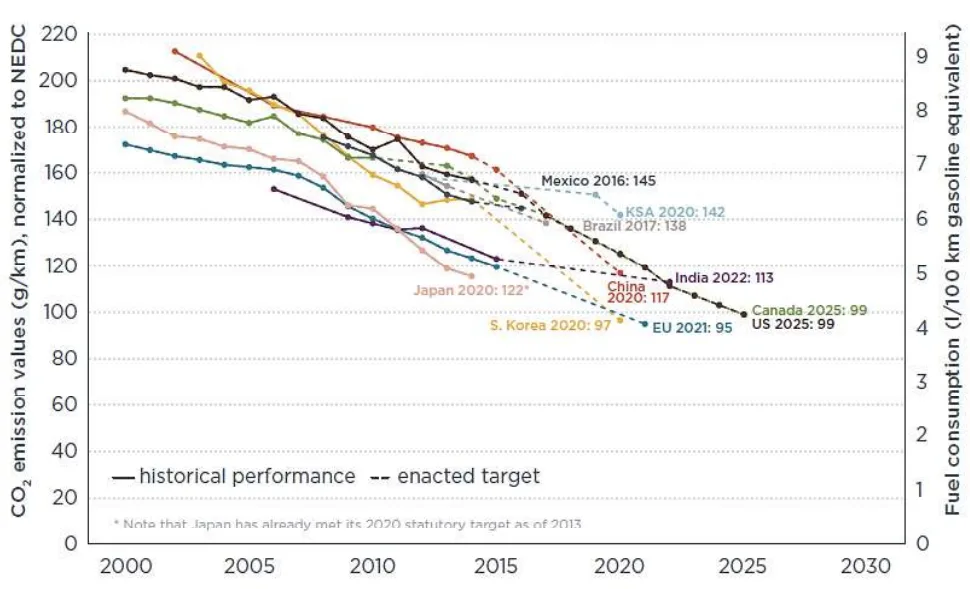

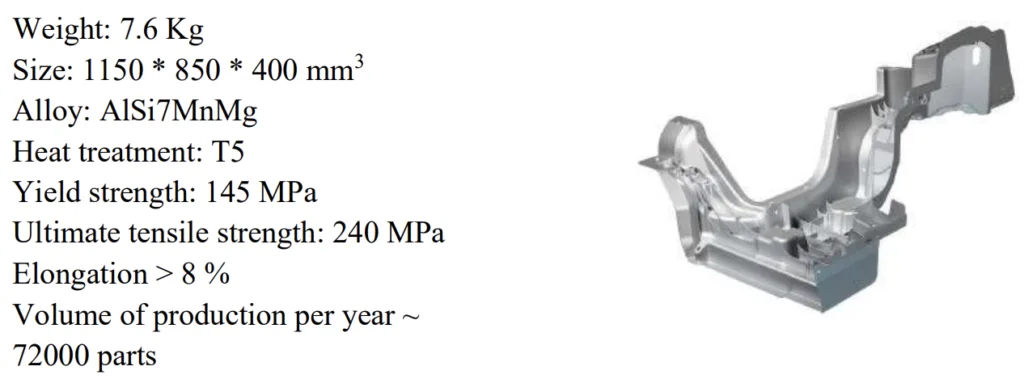

In response to the automotive sector's demand for reduced vehicle weight to improve fuel efficiency and lower CO2 emissions, this thesis investigates a cost-efficient process route for mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings, aiming to replace heavier steel components. The research begins with a cost calculation study to identify key cost drivers in High Pressure Die Casting (HPDC) and RheoMetalTM processes, focusing on factors like machine type, alloy selection, heat treatment, vacuum application, and die life. The study evaluates various aluminum alloys, including Al-Si, Al-Mg-Si, and Al-Mg-Fe families, for their suitability in structural castings without heat treatment. Experimental approaches include producing test plates and parts using HPDC and RheoMetalTM, followed by mechanical testing such as tensile tests, bending tests, density measurements, and self-piercing riveting (SPR) analysis to assess crash resistance and joint integrity. The thesis compares HPDC and RheoMetalTM processes to determine a cost-efficient manufacturing method for mass-produced, thin-walled structural aluminum body castings.

3. Research Background:

Background of the Research Topic:

The automotive industry is driven by the need to reduce CO2 emissions and improve fuel efficiency, leading to approaches focused on vehicle weight reduction. Replacing steel sheets with lighter aluminum castings is a key strategy, offering functional integration and weight savings. However, mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings is less economical due to material costs. This research addresses the need for a cost-efficient process route to facilitate the broader adoption of aluminum castings in automotive structures.

Status of Existing Research:

Automotive OEMs have integrated aluminum castings into structural body parts, utilizing standard Al-Si casting alloys. Casting methods like high pressure die casting, gravity die casting, low pressure die casting, and green sand casting are widely used. High pressure die casting is particularly attractive for large volume production due to its short cycle time. Semi-solid casting methods, including thixocasting and rheocasting, offer advantages such as reduced gas porosities and improved mechanical properties. RheoMetalTM process, a type of rheocasting, utilizes enthalpy exchange for slurry creation, differing from temperature-controlled methods.

Necessity of the Research:

Existing methods for producing structural aluminum castings, particularly using Al-Si alloys, often require expensive heat treatments to meet mechanical property requirements (Rp0.2 > 120 MPa, Rm > 180 MPa, Elongation > 10%). There is a need to explore cost-efficient alternatives, such as as-cast alloys and advanced casting processes like RheoMetalTM, to reduce or eliminate heat treatment costs while maintaining structural integrity and crash resistance. The research aims to identify alloys and processes suitable for mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings in a cost-effective manner.

4. Research Purpose and Research Questions:

Research Purpose:

The primary research purpose is to develop a cost-efficient process route for the mass production (1,000,000 - 2,000,000 parts) of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings. This involves investigating and optimizing both alloy selection and casting processes to minimize production costs while meeting stringent mechanical and structural requirements for automotive applications.

Key Research:

- To identify the main cost drivers in the production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings using HPDC and RheoMetalTM processes.

- To evaluate the suitability of different aluminum alloys, particularly as-cast alloys, for structural automotive castings in terms of mechanical properties, crash resistance, and rivetability.

- To optimize process parameters for HPDC and RheoMetalTM casting processes to enhance casting quality and reduce production costs.

- To compare the cost-efficiency and performance of HPDC and RheoMetalTM processes for mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings.

Research Hypotheses:

- Utilizing alloys that do not require heat treatment, such as Al-Mg-Si and Al-Mg-Fe families, can lead to a more cost-efficient production route compared to traditional Al-Si alloys requiring T7 heat treatment.

- The RheoMetalTM casting process, due to its potential for longer die life and reduced material usage, can offer a more cost-efficient alternative to HPDC for mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings.

- MYFORD alloy, with its modified composition and enhanced rheocastability, will demonstrate superior performance in RheoMetalTM casting and achieve comparable or better mechanical properties and crash resistance compared to standard alloys in HPDC.

5. Research Methodology

Research Design:

The research employs a comparative experimental design, evaluating two primary casting processes (HPDC and RheoMetalTM) and various aluminum alloys and heat treatment combinations. Cost calculation studies are integrated to assess the economic viability of different process routes.

Data Collection Method:

- Cost Calculation Study: A detailed cost calculation tool, provided by Bühler AG, was used to analyze the cost implications of different factors in HPDC and RheoMetalTM processes.

- Mechanical Testing: Tensile tests (uniaxial and 3-point bending), density measurements (Archimedes' principle), and self-piercing riveting (SPR) tests were conducted to evaluate material properties, crash resistance, and joint performance.

- Microstructural Analysis: SEM-EDS and optical microscopy were used to characterize the microstructure and identify defects in the castings.

- Spectrochemical Analysis: Optical Emission Spectroscopy was used to verify the chemical composition of the alloys.

Analysis Method:

- Statistical Analysis: Minitab and Microsoft Excel were used for statistical analysis of mechanical testing data, including ANOVA and graphical representations (box plots, charts) to compare different alloys and processes.

- Cost Analysis: The cost calculation tool was used to compare the cost-efficiency of different scenarios, considering factors like alloy, process, die life, and heat treatment.

- Microstructural Evaluation: Qualitative and quantitative analysis of microstructural images to assess grain size, phase distribution, and defect presence.

Research Subjects and Scope:

- Materials: Aluminum alloys from Al-Si, Al-Mg-Si, and Al-Mg-Fe families, including AlSi10MnMg, AlSi9MnMoZr, AlMg4Fe2, MYFORD, AlSi7Mg0.3, EN AB-42000, AlMg5Si2Mn, AlMg6Si2MnZr. DP600 steel sheets were used for SPR testing.

- Casting Processes: High Pressure Die Casting (HPDC) and RheoMetalTM process.

- Test Specimens: Test plates (3.1mm and 2.5mm thickness) and a complex geometry part (simulating a shock tower) were produced at different suppliers (Foundry Institute (GI) of RWTH Aachen University, Magna BDW technologies Soest GmbH, Comptech AB).

- Testing Scope: Evaluation of mechanical properties, crash resistance potential, and rivetability of the castings produced by HPDC and RheoMetalTM processes using various alloys and heat treatments.

6. Main Research Results:

Key Research Results:

- Cost Calculation Study: Heat treatment and die life were identified as major cost drivers in HPDC. RheoMetalTM process showed potential for cost reduction due to extended die life. As-cast alloys like AlSi9MnMoZr and MYFORD were found to be cost-efficient alternatives by eliminating heat treatment.

- Mechanical Properties: MYFORD and AlSi10MnMg-T7 alloys demonstrated superior mechanical properties, meeting or exceeding the requirements for the 2020 Ford explorer shock tower. RheoMetalTM processed parts showed slightly lower crash resistance potentials compared to HPDC parts.

- Crash Resistance: AlMg4Fe2 and MYFORD alloys exhibited the highest crash resistance potentials in both HPDC and RheoMetalTM processes.

- Rivetability: AlMg4Fe2 and MYFORD alloys showed better rivetability compared to other alloys. AlSi10MnMg-T7 also demonstrated good rivetability. RheoMetalTM processed parts showed comparable rivetability to HPDC parts.

- Microstructural Analysis: HPDC castings showed dendritic microstructures, while RheoMetalTM castings exhibited globular microstructures. Shrinkage porosities were observed in some alloys, particularly AlMg5Si2Mn and AlMg6Si2MnZr in HPDC. MYFORD alloy in RheoMetalTM process showed fine globular microstructure with minimal defects.

Analysis of presented data:

- Figure 5.1: Illustrates the influence of melt flow velocity on the total elongation of AlMg4Fe2 alloy in HPDC, showing a slight increase in elongation with higher velocity.

- Figure 5.7 & 5.8: Show force-displacement and energy-displacement charts for Al-Si alloys in HPDC, indicating AlSi10MnMg-T7 and AlMg4Fe2 alloys have higher crash resistance.

- Figure 5.9 & 5.10: Present simulated force-displacement and energy-displacement charts for Al-Si alloys, validating the experimental trends.

- Figure 5.11 & 5.12: Show force-displacement and energy-displacement charts for all HPDC alloys, highlighting AlMg4Fe2 and AlSi10MnMg-T7 as top performers in crash resistance.

- Figure 5.15: Presents force-displacement chart for HPDC alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations for SPR joints, showing performance variations.

- Figure 6.4 & 6.5: Show force-displacement and energy-displacement charts for RheoMetalTM alloys, indicating AlMg4Fe2 alloy has higher crash resistance.

- Figure 6.6 & 6.7: Present force-displacement and energy-displacement charts comparing RheoMetalTM alloys, highlighting MYFORD and AlMg4Fe2 as top performers in crash resistance.

- Figure 6.8: Shows force-displacement chart for AlMg4Fe2 alloy in RheoMetalTM process for SPR joints, demonstrating joint performance.

Figure Name List:

- Figure 0.1: The JMatPro® simulations of the AlMg4FeX alloy with (a) X= 1.3% Fe and (b) X= 0.5% Fe (MYFORD).

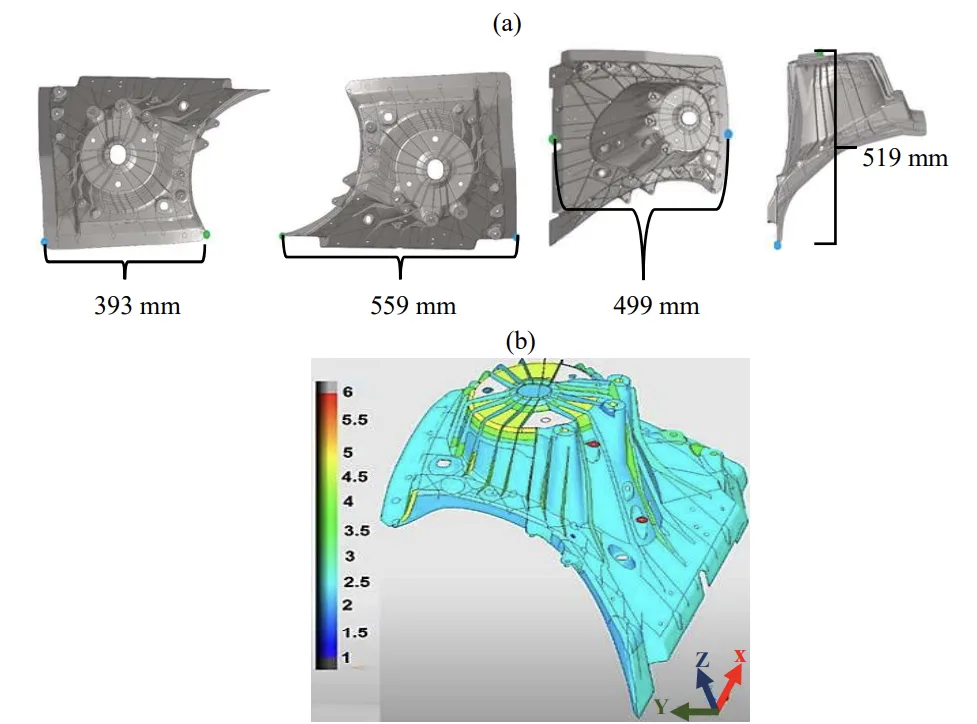

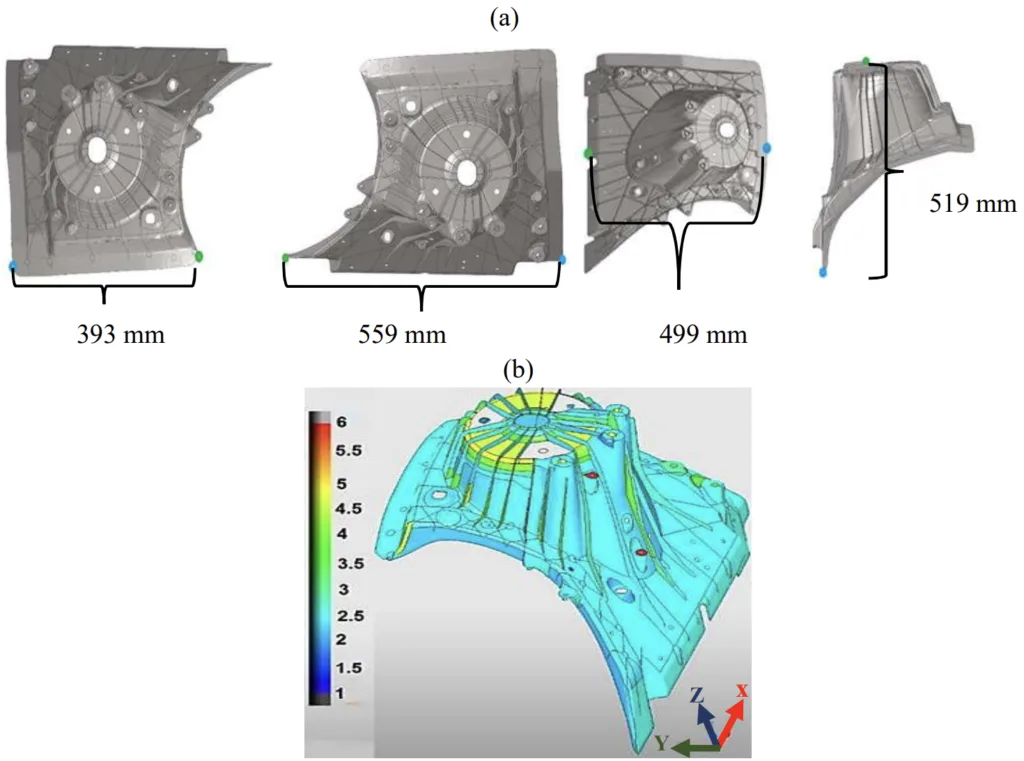

- Figure 0.2: (a) The geometrical dimensions and (b) the thickness distribution (mm) of the 2020 Ford explorer aluminium shock tower.

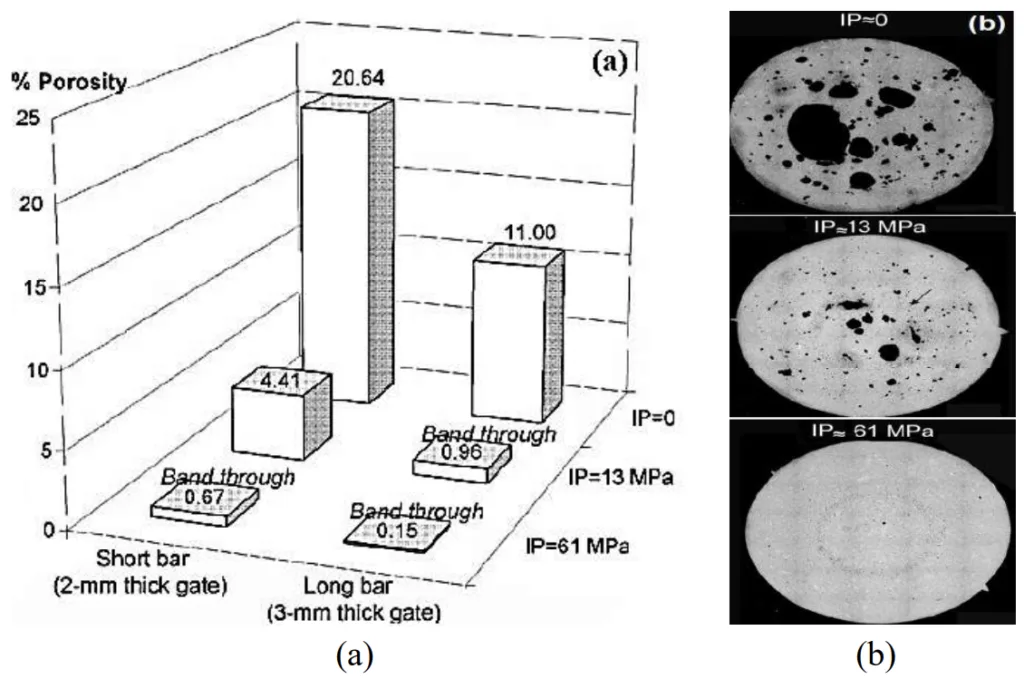

- Figure 2.7: (a) The effect of the gate velocity on the pore fraction and on (b) the mechanical properties (modified from (18)).

- Figure 2.8: The effect of the intensification pressure (IP) on (a) the porosity content and (b) the macrostructures of the high pressure die castings (modified from (21)).

- Figure 2.10: The structure of the cold flake and its accompanying oxide layer (28).

- Figure 2.11: Shear bands in a HPDC test bar of an AlSi7Mg0.3 alloy (30).

- Figure 2.12:The typical die casting microstructures of the AlSi7 alloy that are formed using (a) the conventional liquid die casting process and (b) the semi-solid casting process (38).

- Figure 2.22: The influence of the rotation speed on the (a) average size of the α1-Al phase, (b) the fraction of the α1-Al phase, (c) the slurry formation time and the cooling rate.

- Figure 2.23: The influence of the melt superheat on the (a) average size of the α1-Al phase, (b) the fraction of the α1-Al phase, (c) the slurry formation time and the cooling rate.

- Figure 2.24: The combined influence of the melt superheat and the EEM amount on (a) the average size of the α1-Al phase, (b) the fraction of the α1-Al phase, (c) the slurry formation time and the cooling rate.

- Figure 2.25: (a) Eutectic rich bands and (b) porosity bands that can develop in Rheocast parts (54).

- Figure 2.26: The microstructure of a rheocast radio filter (a) near the gate and (b) near the vent (49).

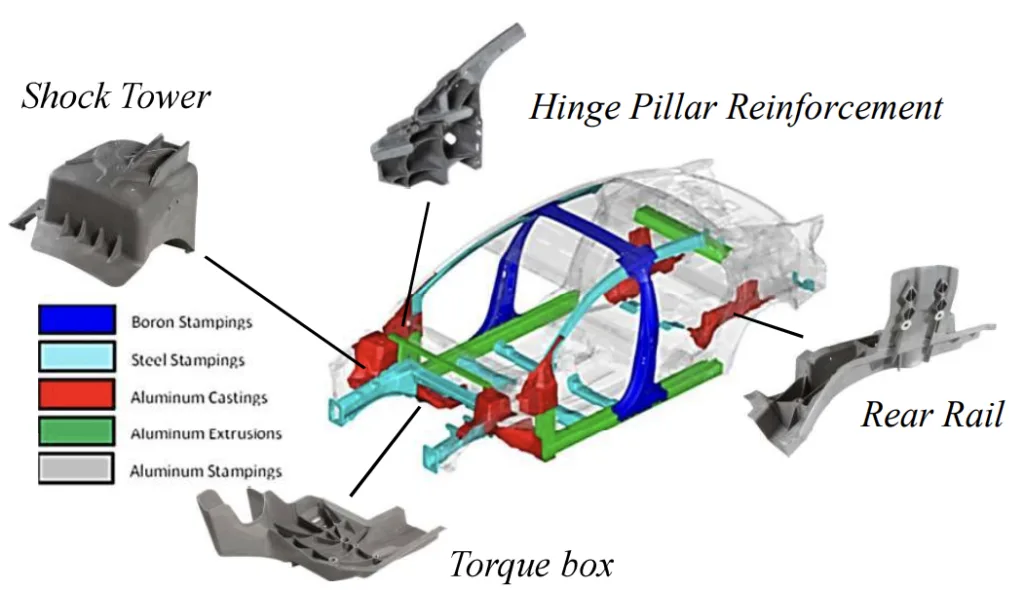

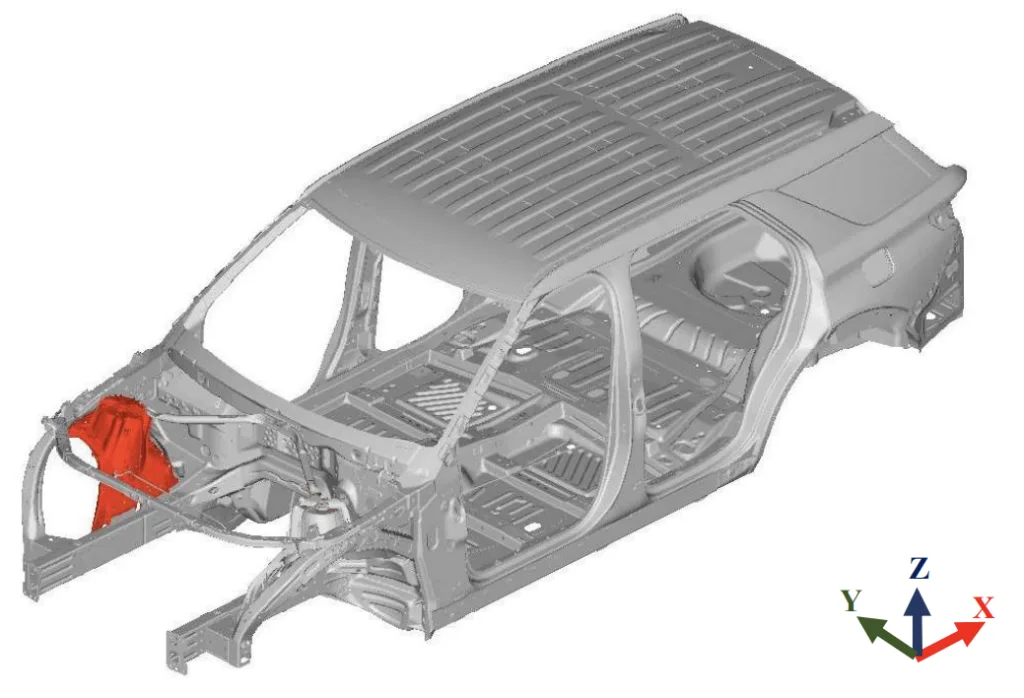

- Figure 3.1: An aluminium shock tower (red) in the 2020 Ford explorer’s body.

- Figure 3.2: The outline of the expenses of investment section in the calculation tool.

- Figure 3.3:The aluminium alloy prices per ton in $ from January 2016 till December 2018 according to the London Metal Exchange (modified from (71)).

- Figure 4.1: (a) The geometrical dimensions and (b) the thickness distribution (mm) of the 2020 Ford explorer aluminium shock tower.

- Figure 4.2: The experimental approach.

- Figure 4.3: The HPDC setup consisting of (a) the holding electric resistance furnace, (b) the shot sleeve, ladle & robot arm and (c) the vacuum assisted die.

- Figure 4.4: The dimensions of the plates from supplier 1.

- Figure 4.5: The die cavity’s design for the HPDC trials at supplier 1.

- Figure 4.6: The dimensions of the plates from supplier 2.

- Figure 4.7: The setup consisting of (a) the induction furnace, (b) the EEM production station and (c) the slurry production station.

- Figure 4.8: (a) The EEM’s height before adjustment (casted EEM), (b) the sawing machine and (c) the EEM’s height after adjustment (hEEM).

- Figure 4.9: The slurry making process.

- Figure 4.10: The die cavity’s design for the RheoMetalTM casting trials at supplier 1.

- Figure 4.11: (a) The top view, (b) the bottom view and the (c) side view of the part.

- Figure 4.12: (a) The 800-ton HPDC machine, (b) the die and the second robot arm and the (c) moving tray.

- Figure 4.13: The different pre-steps for the production of the semi-solid slurry.

- Figure 4.14: The phase diagram of the standard AlMg4Fe2 alloy with 1.5-1.7%Fe and 4.5% Mg (modified from (77)).

- Figure 4.15: The suggested enhancement to the standard AlMg4Fe2 alloy, as demonstrated by the circle and the arrow (modified from (77)).

- Figure 4.16: The JMatPro® simulation for the Al-Mg-Fe alloy with a 1.3%Fe.

- Figure 4.17: The JMatPro® simulation for the MYFORD alloy.

- Figure 4.18: The exact geometrical dimensions of the Type E sample in mm (6).

- Figure 4.19: The exact geometrical dimensions of the mini samples in mm.

- Figure 4.20: A 3D model of the supplier 1 plate and the tensile testing samples.

- Figure 4.21: (a) The initial dimension, (b) the extra 1 mm and (c) the final dimension of the (i) mini sample and the (ii) Type E sample in mm.

- Figure 4.22: The top and side views of a mini sample (a)before and (b)after preparation.

- Figure 4.23: The extracted tensile test samples from the (a) supplier 1 plates, (b) supplier 2 plates and (c) supplier 3 parts.

- Figure 4.24: The tensile test setup for the mini and the Type E samples.

- Figure 4.25: The different test speeds during tensile testing.

- Figure 4.26: (a) The setup of the 3-point bending test and (b) the important dimensions (4).

- Figure 4.27: The dimensions of the bending test samples.

- Figure 4.28: The location of the 3-point bending test samples in the (a) supplier 1 plates, (b) supplier 2 plates and (c) supplier 3 parts.

- Figure 4.29: (a) An example of a bending angle and (b) the bending angle measuring tool.

- Figure 4.30: The setup for the density measurement trials.

- Figure 4.31: The positions of the SPR samples in (a) the supplier 1 plates (thickness = 3.1 mm) and (b) the supplier 2 plates (thickness = 2.65 mm).

- Figure 4.32: An example of a good SPR joint (86).

- Figure 4.33: The flat die design (88).

- Figure 4.34: Henrob SPR setup for manual trials.

- Figure 4.35: (a) The joint making using the SPR process (86) and (b) the connected structures.

- Figure 4.36: An example of the (a) circumferential cracks, (b) deep radial cracks and (c) light radial cracks.

- Figure 4.37: The 25 mm * 100 mm lap shear test samples.

- Figure 4.38: The SPR trials on the parts from supplier 3.

- Figure 4.39: The location of the extracted samples from (a) the supplier 1 plates, (b) the supplier 2 plates and (c) the supplier 3 parts.

- Figure 4.40: An example of a hot mounted sample.

- Figure 4.41: The positions a, b and c in the supplier 1 plates.

- Figure 4.42: (a) The total elongation values (%) of the different samples and (b) their respective positions in the plates. (Designation from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 4.43: (a) The total elongation values (%) of the different sample types and (b) the outline of the samples in one of the investigated plates. (Designation from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 4.44: (a) The effect of the sample orientation on the total elongation values (%), (b) the positions of the longitudinal and perpendicular samples in respect to each other, (c) the location of the extracted longitudinal samples and (d) the location of the extracted perpendicular samples. (Designation from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 4.45: The consistency of the HPDC process at supplier 1 using the (a) Type E samples and the (b) mini tensile test samples. (Designation from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.1: The influence of the melt flow velocity on the total elongation (%) of AlMg4Fe2. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.2: The influence of the melt flow velocity on the total elongation (%) of (a) AlSi7Mg0.3 and (b) AlMg6Si2MnZr. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.3: The influence of the melt flow velocity on the total elongation (%) of AlMg5Si2Mn. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.4: The influence of the intensification pressure on the total elongation (%) of AlMg4Fe2. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.5: The comparison between the different HPDC alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations in terms of their (a) Rp0.2 values (MPa), (c) Rm values (MPa) and (c) total elongation values (%). (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.6: The comparison between the different HPDC alloys in terms of their (a) Rp0.2 values (MPa), (c) Rm values (MPa) and (c) total elongation values (%). (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 5.7: The force-displacement chart of the Al-Si alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.8: The energy-displacement diagram of the Al-Si alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.9: The simulated force-displacement chart of the Al-Si alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.10 : The simulated energy-displacement chart of the Al-Si alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.11: The force-displacement chart of all the HPDC alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations that were used for the casting of the plates. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.12: The energy-displacement chart of all the HPDC alloys and alloy-heat treatment combinations that were used for the casting of the plates. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 5.13: The force-displacement chart of the HPDC alloys that were used at supplier 3. (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 5.14: The energy-displacement chart of the HPDC alloys that were used at supplier 3. (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 6.1: The influence of the intensification pressure on the total elongation (%) of the AlMg4Fe2 alloy. (Designations from Table 4.5, P58)

- Figure 6.2: The comparison between the different RheoMetalTM alloys in terms of their (a) Rp0.2 values (MPa), (c) Rm values (MPa) and (c) total elongation values (%). (Designations from Table 4.5, P58)

- Figure 6.3: The comparison between the different RheoMetalTM alloys in terms of their (a) Rp0.2 values (MPa), (c) Rm values (MPa) and (c) total elongation values (%). (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 6.4: The force-displacement chart for the RheoMetalTM alloys that were used for the casting of the plates at supplier 1. (Designations from Table 4.5, P58)

- Figure 6.5: The energy-displacement chart for the RheoMetalTM alloys that were used for the casting of the plates at supplier 1. (Designations from Table 4.5, P58)

- Figure 6.6: The force-displacement chart of the RheoMetalTM alloys that were used at supplier 3. (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 6.7: The energy-displacement chart of the RheoMetalTM alloys that were used at supplier 3. (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 6.8:The force-displacement chart for D-(50-4.63-575-1000)-R. (Designation from Table 4.5, P58)

- Figure 7.1: The shrinkage porosities in the microstructures of (a) AlMg5Si2Mn (B-(3.5-650)) and (b) AlMg6Si2MnZr (C-(3.5-650)). (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 7.2: The 500x microstructural images of (a) AlSi10MnMg-F and (b) AlSi10MnMg-T7. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 7.3: Dislocations overcoming a precipitate a) by shearing or b) by looping (Orowan mechanism) and c) the effect of the dislocations passing mechanism on the total yield strength of the alloy (65).

- Figure 7.4: (a) The Rp0.2 values (MPa), (b) the Rm values (MPa) and (c) the total elongation values (%) of AlSi10MnMg-T7. (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 7.5: The 200x microstructural images of (a) AlSi10MnMg (H) and of (b) AlMg4Fe2 (D-(3-650)). (Designations from Table 4.3, P54)

- Figure 7.6: The 500x microstructural images of (a) AlMg4Fe2 (F-740C) and of (b) MYFORD (G-755C). (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 7.7: The total elongation (%) chart for the investigated RheoMetalTM alloys at supplier 1. (Designation from Table 4.5, P58)

- Figure 7.8: The 500x microstructural images of (a) the AlMg4Fe2 alloy (F-750R-1100-30C) and of (b) the MYFORD alloy (G-755R-1100-30C). (Designations from Table 4.9, P65)

- Figure 7.9: The crash resistance potentials of the RheoMetalTM parts (red) and the parts produced by HPDC (black).

7. Conclusion:

Summary of Key Findings:

This research concludes that for mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings, MYFORD alloy processed by HPDC is the most cost-efficient route. MYFORD alloy, an Al-Mg-Fe alloy variant, offers comparable mechanical properties, crash resistance, and rivetability to the currently used AlSi10MnMg-T7 alloy in HPDC, but without the need for expensive heat treatment. While RheoMetalTM process offers potential cost benefits through extended die life, HPDC demonstrates superior crash resistance for thin-walled castings.

Academic Significance of the Study:

This study provides a comprehensive handbook-level analysis of cost-efficient process routes for thin-walled structural aluminum body castings. It systematically evaluates various alloys and casting processes, contributing valuable data and insights into the optimization of aluminum die casting for automotive structural components. The research highlights the importance of alloy selection and process parameter optimization in achieving both high performance and cost-effectiveness in mass production.

Practical Implications:

The findings suggest that automotive manufacturers can adopt MYFORD alloy in HPDC as a cost-efficient alternative to AlSi10MnMg-T7 for thin-walled structural body castings, eliminating heat treatment costs without compromising structural integrity. The optimized process parameters identified for HPDC and RheoMetalTM processes offer practical guidelines for industrial implementation. The research also underscores the potential of RheoMetalTM process for thicker and smaller parts, suggesting avenues for future applications.

Limitations of the Study and Areas for Future Research:

- The RheoMetalTM casting trials at supplier 1 were less efficient, potentially affecting the direct comparison with HPDC. Further optimization of RheoMetalTM process parameters, particularly melt superheat, %EEM, and rotation speed, could enhance its performance and cost-efficiency.

- Corrosion testing was not included in this study. Future research should evaluate the corrosion resistance of MYFORD alloy and other candidate alloys to ensure long-term durability in automotive applications.

- Further investigation into extending die life through minimal quantity lubrication (MQL) technology and advanced die materials could further reduce production costs in HPDC.

- Exploring the performance of RheoMetalTM process for thicker and smaller structural parts could unlock its full potential and broaden its application range in automotive manufacturing.

8. References:

- Rio Tinto. Aluminium: Your guide to automotive innovation. [Online] 2019. [Cited: November 11, 2019.]

- Aluminium Rheinfelden GmbH. Handbook- Primary aluminum casting alloys. [Online] 2017. [Cited: September 12, 2019.]

- Stena Aluminium. Aluminium alloy EN AB-42000. [Online] [Cited: October 30, 2019.]

- Verband der Automobilindustrie (VDA). VDA 238-100 : Plate bending test for metallic materials. Berlin : VDA, 2010.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 6892-1. METALLIC MATERIALS - TENSILE TESTING - Part 1: Method of test at room temperature. Geneva : ISO, 2016.

- Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN). DIN 50125: Prüfung metallischer Werkstoffe- Zugproben. Berlin : Beuth Verlag, 2016.

- Hoegh-Guldberg, O., et al. Impacts of 1.5ºC Global Warming on Natural and Human Systems. [book auth.] V. Masson-Delmotte, et al. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change. Geneva : The intergovernmental panel on climate change (ipcc), 2018.

- Yang, Z. and Bandivadekar, A. 2017 Global update: Light-duty vehicle greenhouse gas and fuel economy standards. [Online] [Cited: May 29, 2018.]

- Ducker Worldwide LLC. 2015 North American Light Vehicle Aluminum Content Study. [Online] 2014. [Cited: November 7, 2019.]

- Goede, M., et al. Super Light Car—lightweight construction thanks to a multi-material design and function integration. European Transport Research Review. 2009, Vol. 1, 1, pp. 5-10.

- NADCA Design. Die Casting vs Metal Extrusion. [Online] NADCA Design. [Cited: November 11, 2019.]

- Yuksel, G., et al. MMLV: NVH Sound Package Development and Full Vehicle testing, SAE Technical Paper 2015-01-1615. SAE International. 2015.

- European Aluminum Association. The Aluminum Automotive manual, Manufacturing-casting methods. [Online] 2002. [Cited: May 23, 2019.]

- The American Foundry Society Technical Dept. Aluminium Alloys. Engineered casting solutions. 2006, Vol. 8, 4, pp. 30-34.

- AZoM. Aluminium Casting Techniques - Sand Casting and Die Casting Processes. [Online] 2002. [Cited: July 4, 2018.]

- Foundry Lexicon. [Online] Foundry Lexicon. [Cited: April 24, 2019.]

- Karban, Robert. The effects of intensification pressure, gate velocity, and intermediate shot velocity on the internal quality of aluminum die castings. s.l. : Purdue University, PHD thesis, 2000.

- D. R. Gunasegaram, B. R. Finnin, F. B. Polivka. Melt flow velocity in high pressure die casting: its effect of microstructure and mechanical properties in an Al-Si alloy. Materials Science and Technology. 2007, Vol. 23, 7, pp. 847-856.

- Herman, E.A. Gating Die Casting Dies. Rosemont,IL : NADCA, 1996.

- Fiorese, E, et al. Influence of injection parameters on the porosity and tensile properties of high-pressure die cast Al-Si alloys: A review. International Journal of metalcasting. 2015, Vol. 1, 9, pp. 43-53.

- Otarawanna, S., et al. Feeding mechanisms in High-pressure die castings. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2010, Vol. 41, 7, pp. 1836-1846.

- Niu, X.P., et al. Vaccum assisted high pressure die casting of aluminium alloys. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2000, Vol. 105, 1-2, pp. 119-127.

- SUN, S., Yuan, B. and Liu, M. Effects of moulding sands and wall thickness on microstructure and mechanical properties of Sr-modified A356 Aluminum casting alloy. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China. 2012, Vol. 22, 8, pp. 1884-1890.

- Djurdjevic, M.B. and Grzincic, M. The Effect of Major Alloying Elements on the size of secondary dendrite arm spacing in the As-cast Al-Si-Cu Alloys. ARCHIEVES of FOUNDARY ENGINEERING. 2012, Vol. 12, 1, pp. 19-24.

- K. Radhakrishna and S. Seshan. Dendritic arm spacing and mechanical properties of Aluminium Alloy castings. Cast Metals. 1989, Vol. 2, 1, pp. 34-38.

- Hartlieb, M. High Integrity Die Casting: A Holistic Approach To Improved Die Casting Quality. [Online] [Cited: November 7, 2019.]

- Pasligh, Niels. Hybride formschlüssige Strukturverbindungen in Leichtbaustrukturen aus Stahlblech und Aluminiumdruckguss. s.l. : Giesserei-Instiut der RWTH Aachen, Dissertation, 2011.

- Ahamed, A. and Kato, H. Influence of Casting Defects on Tensile properties of ADC12 Aluminum Allo Die-Castings. Materials Transactions. 2008, Vol. 49, 7, pp. 1621-1628.

- Cao, X. and Campbell, J. Oxide inclusion defects in Al-Si-Mg cast alloys. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly. 2005, Vol. 44, 4, pp. 435-448.

- C.M.Gourlay and A.K.Dahle. Dilatant shear bands in solidifying metals. Nature. 2007, Vol. 445, 7123, pp. 70-73.

- Ghosh, A. Segregation in cast products. SADHANA. 2001, Vol. 26, 1-2, pp. 5-24.

- Midson, S.P. and Jackson, A. A comparison of Thixocasting and Rheocasting. 67th World Foundry Congress (wfc06): Casting the Future. Harrogate, UK : Institute of Cast Metals Engineers, 2006, pp. 1081-1090.

- Midson, S.P., Thornhill, L.E. and Young, K. Proc.5th Int.Conf. On Semi-Solid Processing of Alloys & Composites. Golden, Colorado : Colorado School of Mines, 1998. p 181.

- Jolly, M. Prof. John Campbell's Ten Rules for Making Relaible Castings. JOM. 2005, Vol. 57, 5, pp. 19-28.

- Nafisi, Shahrooz and Ghomashchi, Reza. Grain refining of conventional and semi-solid A356 Al-Si alloy. s.l. : Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 2006. Vol 174 pp 371-383.

- Flemings, M.C. Behaviour of metal alloys in the semi-solid state. Metallurgical Transactions A. 1991, Vol. 22, 5, pp. 957-981.

- McCartney, D.G. Grain refining of aluminium and its alloys using inoculants. International Material Reviews. 1989, Vol. 13, 5, pp. 247-260.

- Pola, A, Toci, M and Kapronas, P. Microstructure and properties of Semi-Solid Aluminum Alloys: A literature review. 2018, Vol. 8, 3, p. 181.

- Gerhard, H., et al. Semi-solid Forming of Aluminium and Steel-Introduction and overview. [book auth.] H. Gerhard and R Kopp. Thixoforming: Semi-Solid Metal Processing. Weinheim : WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2009.

- Czerwinski, F. The basics of modern semi-solid metal processing. JOM. 2006, Vol. 58, 6, pp. 17-20.

- Yurko, James A, Martinez, Raul A. and C.Flemmings, Merton. The use of Semi Solid Rheocasting (SSR) for Aluminum automotive castings. s.l. : SAE paper 2003-01-0433., 2003.

- Fan, Z. Semisolid metal processing. International Materials Reviews. 2002, Vol. 47, 2, pp. 49-85.

- Kirkwood, D. H., et al. Semi-Solid Processing of Alloys. Berlin, Heidelberg : Springer, 2010.

- Modigell, M., Annalisa, P. and Marialaura, T. Rheological Characterization of Semi-Solid Metals: A Review. Metals. 2018, Vol. 8, 4, pp. 245-268.

- Basner, T. Rheocasting of semi solid A357 Aluminum, SAE paper :2000-01-0059. SAE International. 2000.

- Midson, S.P. Rheocasting processes for Semi-Solid Casting of Aluminium Alloys. Die Casting Engineer. 2006, Vol. 1, pp. 48-51.

- C.P, Hong, and J.M, Kim. Development of Advanced Rheocasting Process and its applications. Solid State Phenomena. 2006, Vols. 116-117, pp. 44-53.

- Patent: WO/2006/062, 482. A method of and a device for producing a liquid-solid metal composition. Filling date: 2006, Inventors: Wessen, M; Cao, H.

- Payandeh, Mostafa. Rheocasting of Aluminium Alloys, Process and components characteristics. Jönköping university, PhD thesis, 2016.

- H.Cao, M.Wessén & O.Granath. Effect of injection velocity on porosity formation in Al rheocast component using Rheometal process. International Journal of Cast Metals Research. 2010, Vol. 23, 3, pp. 158-163.

- Lee, J., Seok, H. and Lee, H. Effect of the Gate Geometry and the Injection Speed on the Flow. Metals and Materials International. 2003, Vol. 9, 4, pp. 351-357.

- O.Granath, M.Wessen and H.Cao. Determining the effect of the slurry process parameters on semisolid A356 alloy microstructures produced by Rheometal process. International Journl of Cast Metals Research. 2008, Vol. 21, 5, pp. 349-356.

- Bladh, M., Wessen, M. and Dahle, A.K. Shear band formation in shaped Rheocast Aluminium component at various plunger velocities. Trans.Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 2010, Vol. 20, 9, pp. 1749-1755.

- Payandeh, M., Jarfors, A. and Wessen, M. Influence of microstructural inhomogenity on fracture behaviour in SSM-HPDC Al-Si-Cu-Fe component with low Si content. Solid state phenomena. Vols. 216-217, pp. 67-74.

- Zhu, Baiwei. On the influence of Si on Anodising and Mechanical properties of Cast Aluminium Alloys. Jönköping University, Licentiate thesis, 2017.

- Hegde, S. and Prabhu, K.N. Modification of eutectic silicon in Al-Si alloys. Journal of Materials science. 2008, Vol. 43, 9, pp. 3009-3027.

- Zhu, X., et al. The effects of varying Mg and Si levels on the microstructural inhomogenity and eutectic Mg2Si morphology in die-cast Al-Mg-Si alloys. Journal of Materials Science. 2019, Vol. 54, 7, pp. 5773-5787.

- Yuan, W. and Liang, Z. Effect of Zr addition on properties of Al-Mg-Si aluminum alloy used for all aluminium alloy conductor. Materials and Design. 2011, Vol. 32, 8, pp. 4195-4200.

- Ji, S., et al. Effect of iron on the microstructure and mechanical property of Al-Mg-Si-Mn and Al-Mg-Si diecast alloys. Materials Science and Engineering A. 2013, Vol. 564, pp. 130-139.

- Hwang, J.Y., Doty, H.W. and Kaufman, M.J. The effects of Mn additions on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Si-Cu casting alloys. Materials Science and Engineering A. 2008, Vol. 488, 1-2, pp. 496-504.

- Murray, J.L. and McAlister, A.J. Bulletin of Alloy Phase Diagrams. 1984, Vol. 5, 1, pp. 86-112.

- Zeru, G.T., Mose, B.R. and Mutuli, S.M. The fluidity of a Model Recycle-Friendly Al-Si Cats Alloy for Automotive Engine Cylinder Head Application. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT). 2014, Vol. 3, 8.

- Timelli, G. and Bonollo, F. Fluidity of aluminium die casting alloys. International Journal Of Cast Metals Research. 2007, Vol. 20, 6, pp. 304-311.

- Gwózdz, M and Kwapisz, K. Influence of ageing process on the microstructure and mechanical properties of aluminium-silicon cast alloys - Al-9%Si-3%Cu and Al-9%Si-0.4%Mg. s.l. : Jönköping University, Bachelor thesis, 2008.

- Mohamed, A.M.A. and Samuel, F.H. A Review on the Heat Treatment of Al-Si-Cu/Mg Casting Alloys. Heat treatment - Conventional and novel applications. s.l. : IntechOpen, 2012, pp. 55-72.

- Katgerman, L and Eskin, D. Hardening, annealing and aging. [book auth.] G.E Totten and D.S Mackenzie. Handbook of Aluminum: Vol. 1: Physical Metallurgy and Processes. New York : Marcel Dekker, Inc, 2003, pp. 269-271.

- Bühler AG. Carat. The solution with highest value creation for sophisticated parts. [Online] 2018. [Cited: May 24, 2019.]

- Tecnopres. Hydraulic 4 columns Trimming presses. [Online] 2018. [Cited: May 24, 2019.]

- KMA Umwelttechnik GmbH. KMA press release GIFA 2007. [Online] 2007. [Cited: November 8, 2019.]

- STØTEK Inc. Holding Furnace (STE) / (STET). [Online] STØTEK Inc. [Cited: July 27, 2018.]

- The London Metal Exchange. LME Aluminum alloy. [Online] The London Metal Exchange, 2019. [Cited: January 24, 2019.]

- Kaufmann, H. and Uggowitzer, P.J. Metallurgy and Processing of High Integrity Light Metal Pressure Castings. Berlin : SCHIELE & SCHÖN, 2014.

- Han, Q., Kenik, E.A. and Viswanathan, S. Die soldering in aluminium die casting. Office of Scientific & Technical Information Technical Reports. 2000.

- Abdulhadi, H.A., et al. Thermal Fatigue of Die-Casting Dies: An Overview. MATEC Web of Conferences, ICMER 2015. 2016, Vols. 74, 00032.

- Visi-trak worldwide, LLC. High-Q-Cast. [Online] [Cited: July 23, 2018.]

- Midson, S.P., Minkler, R.B. and Brucher, H.G. Gating of Semi-Solid Aluminum Castings. Proc 6th Inter. Conf. on Semi-Solid Processing of Alloys and Composites. Turin, Italy : s.n., 2000, pp. 67-71.

- Aluminium Rheinfelden GmbH. Primary aluminum- HPDC alloys for Structural Casts in Vehicle Construction. [Online] 2017. [Cited: November 8, 2019.]

- Gulliver, G.H. The quantitative effect of rapid cooling upon the constitution of binary alloys. J.Inst.Met. 1909, Vol. 9, pp. 120-157.

- Scheil, E. Comments on the layer crystal formation. Z.Metallkd. 1942, Vol. 34, pp. 70-72.

- ESAB. ESAB knowledge center. [Online] ESAB. [Cited: May 24, 2019.]

- Techni waterjet. Waterjet advantages. [Online] Techni waterjet, 2018. [Cited: May 24, 2019.]

- SMU department of physics. Mechanics laboratery manual - Archimedes' Principle and Buoyancy. [Online] SMU department of physics, 2002. [Cited: March 8, 2019.]

- Abbas, M., St.Pierre, G.R. and Mobley, C.E. Microporosity of Air Cast and Vacuum Cast Aluminium Alloys. AFS Transactions. 1986, Vol. 49, pp. 47-56.

- He, X., Pearson, I. and Young, K. Self-pierce riveting for sheet materials: State of the art. Journal of Materials Processing Technology. 2008, Vol. 199, 1-3, pp. 27-36.

- Li, D., et al. Self-piercing riveting- a review. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology. 2017, Vol. 92, 5-8, pp. 1777-1824.

- Atlas Copco Group. Henrob self-pierce riveting. [Online] [Cited: August 6, 2019.]

- . Henrob BG-Rivet. [Online] [Cited: August 7, 2019.]

- . Henrob die catalogue. [Online] [Cited: November 8, 2019.]

- Stephens, E.V. Mechanical strength of self-piercing riveting. [book auth.] A Chrysanthou and X Sun. Self-Piercing Riveting: Properties, Processes and Applications. s.l. : Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2014.

- Li, D, et al. Influence of Die Profiles and Cracks on Joint Quality and Mechanical Strengths of High Strength Aluminium Alloy Joint. Advanced Materials Research. 2012, Vol. 548, pp. 398-405.

- SCG polymer solutions incorporated. SEM Analysis | SEM-EDS Analysis. [Online] SCG polymer solutions incorporated. [Cited: March 20, 2019.]

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. Spectrochemical analysis. [Online] Encyclopaedia Britannica. [Cited: January 22, 2019.]

- OTARAWANNA, S. and DAHLE, A.K. Casting of aluminium alloys. [book auth.] Roger Lumely. Fundemetals of Aluminium Metallurgy: Production, Processing and Applications. s.l. : Woodhead Publishing Limited, 2011.

- Porcaro, R., et al. The behaviour of a self-piercing riveted connection under quasi-static loading conditions. International Journal of solids and structures. 2006, Vol. 43, 17, pp. 5110-5131.

- Park, J.M., et al. High-strength bulk Al-based bimodal ultrafine eutectic composite with enhanced plasticity. Journal of Materials Research. 2009, Vol. 24, 8, pp. 2605-2609.

- Wang, Q.G., Caceres, C.H. and Griffiths, J.R. Damage by Eutectic Particle Cracking in Aluminum Casting Alloys A356/357. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A. 2003, Vol. 34, 12, pp. 2901-2912.

- Verma, A., et al. Influence of cooling rate on the Fe intermetallic formation in an AA6063 Al alloy. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2013, Vol. 555, pp. 274-282.

- Bielomatik. Minimal Quantity Lubrication (MQL) Systems in Metal Cutting. [Online] [Cited: October 25, 2019.]

- Vicario, I., et al. Development of high pressure die casting dies with internal refrigeration and sensors with reinforced cast steels. International Journal of Manufacturing Engineering. 2014, Vol. 2015, Article ID 287986, pp. 1-10.

9. Copyright:

- This material is "Mohamed Youssef Ahmed Youssef"'s paper: Based on "A cost-efficient process route for the mass production of thin-walled structural aluminum body castings".

- Paper Source: 10.18154/RWTH-2021-03555

This material was summarized based on the above paper, and unauthorized use for commercial purposes is prohibited.

Copyright © 2025 CASTMAN. All rights reserved.