Predicting Long-Term Performance: A Deep Dive into Creep and Ageing in Zinc Die Casting Alloys

This technical summary is based on the academic paper "Interaction of Creep and Ageing Behaviors in Zinc Die Castings" by F. E. Goodwin, L. H. Kallien, and W. Leis, published in the 2016 Die Casting Congress & Tabletop (NADCA).

![Figure 2- Primary (left) and eutectic phase (right) in Alloy 5 dark: Al-rich, bright: Zn-rich [8]](https://castman.co.kr/wp-content/uploads/image-3301.webp)

Keywords

- Primary Keyword: Zinc Die Casting Creep

- Secondary Keywords: Zinc Alloy Ageing, Zamak Creep Properties, High Fluidity Zinc Alloys, Creep Resistance, HPDC Material Science, Norton's Law

Executive Summary

- The Challenge: Predicting the long-term dimensional stability and strength of zinc die-cast parts under constant load is difficult due to the complex and often counter-intuitive interactions between creep and material ageing.

- The Method: The study conducted extensive, long-term creep tests on various zinc alloys (Zamak 2, 3, 5, ZA-8, and a new HF alloy) under different stress, temperature, wall thickness, and ageing conditions.

- The Key Breakthrough: The research quantified that while higher copper content improves creep resistance, prolonged artificial ageing (over 20 hours) can significantly increase creep rates by up to 50 times, contrary to its stabilizing effect on short-term tensile properties.

- The Bottom Line: Engineers must consider both alloy composition and the full thermal history (including post-casting ageing) to accurately predict the long-term creep performance and ensure the reliability of zinc components in demanding applications.

The Challenge: Why This Research Matters for HPDC Professionals

For decades, zinc alloys like Zamak have been a cornerstone of die casting due to their excellent castability, strength, and low cost. However, their application is often limited in components subjected to sustained loads, especially at elevated temperatures, due to a phenomenon called creep—the slow, continuous deformation of a material under constant stress. This can lead to loss of dimensional tolerance and eventual part failure. While previous research has focused on developing creep-resistant alloys, a deep understanding of how standard alloys behave over time, and how their properties change due to ageing, has been lacking. This research addresses that critical knowledge gap, providing the data needed to design more reliable, long-lasting zinc components.

The Approach: Unpacking the Methodology

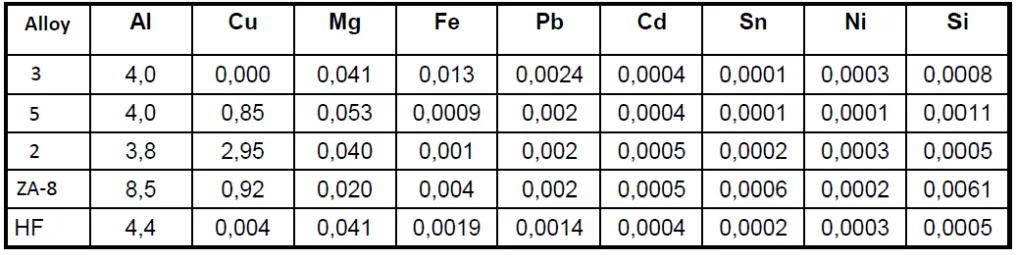

To understand the complex interplay of factors affecting creep, the researchers conducted a comprehensive experimental study on five key zinc die casting alloys: Alloy 3, Alloy 5, Alloy 2, ZA-8, and the newer high-fluidity (HF) alloy.

Method 1: Controlled Creep Testing

Specimens of each alloy were subjected to constant tensile loads at various stress levels. Tests were conducted at both room temperature (with stresses from 40 to 100 MPa) and an elevated temperature of +85°C (with stresses from 12 to 50 MPa) to simulate different service conditions. The resulting strain (deformation) was measured over thousands of hours to generate detailed creep curves.

Method 2: Investigating Ageing and Microstructure

The study examined how the material's history impacts its performance. Creep tests were performed on specimens in both the "as-cast" condition and after artificial ageing at 105°C for periods ranging from 24 hours up to 1000 hours. This was done to simulate the microstructural changes that occur naturally over a product's service life. The effect of casting wall thickness (1.5 mm and 3.0 mm) was also analyzed to understand the influence of grain size and cooling rate.

The Breakthrough: Key Findings & Data

The extensive testing revealed several critical relationships between alloy composition, thermal history, and creep performance.

Finding 1: The Dual Role of Copper and the Counter-Intuitive Effect of Ageing

Copper content proved to be a primary factor in creep resistance. However, the effect of ageing was surprising.

- Copper's Benefit: As shown in Figure 17, alloys with higher copper content exhibited significantly lower creep rates. Alloy 2 (2.95% Cu) showed the best creep resistance, approximately four times better than the copper-free Alloy 3.

- Ageing's Detriment: Contrary to the belief that ageing stabilizes zinc alloys, prolonged heat treatment dramatically increased the creep rate. As seen in Figure 15 for Alloy 5, "the increase of creep rate is nearly 50 times higher after a heat treatment of 1000 hours compared with 24 hours at 105°C." This is because ageing depletes the primary zinc phase of strengthening alloy elements.

Finding 2: Quantifying the Impact of Temperature and Wall Thickness

The study provides clear data on how service temperature and part design influence creep.

- Temperature Dominance: Temperature is a critical accelerator of creep. Figure 13 shows that for Alloy 5, increasing the test temperature from room temperature (25°C) to 85°C increased the creep rate by a staggering "factor of 700."

- Wall Thickness Matters: Thicker sections provide greater creep resistance. Figure 16 demonstrates that for Alloy 5 under the same stress, a 3.0 mm thick specimen exhibited a lower creep strain over time compared to a 1.5 mm specimen. This is attributed to the larger, more creep-resistant grain structure formed during the slower cooling of thicker walls.

Practical Implications for R&D and Operations

- For Process Engineers: This study suggests that adjusting cooling rates (via die temperature and cycle time) to influence grain size may contribute to improved creep resistance in critical components. For thin-wall parts, the HF alloy offers superior filling, but its higher creep rate (shown in Figure 17) must be factored into the design validation.

- For Quality Control Teams: The data in Figure 15 illustrates the dramatic effect of post-casting thermal history on a key mechanical property. This suggests that for components where creep is a critical failure mode, post-casting heat treatments or even long-term storage conditions could become crucial process control points.

- For Design Engineers: The findings provide invaluable data for material selection and lifetime prediction. For applications requiring maximum creep resistance, Alloy 2 is clearly superior to Alloy 3 or 5 (Figure 17). For parts designed to operate at elevated temperatures, the data in Figure 13 is essential for calculating expected deformation and ensuring the component remains within tolerance over its service life.

Paper Details

Interaction of Creep and Ageing Behaviors in Zinc Die Castings

1. Overview:

- Title: Interaction of Creep and Ageing Behaviors in Zinc Die Castings

- Author: F. E. Goodwin, L. H. Kallien, W. Leis

- Year of publication: 2016

- Journal/academic society of publication: 2016 Die Casting Congress & Tabletop, North American Die Casting Association (NADCA)

- Keywords: Zinc Alloys, Die Casting, Creep, Ageing, Zamak, Microstructure, Mechanical Properties

2. Abstract:

Zinc casting alloy research, based on funding from the USA Department of Energy and the NADCA Technology Administration Group has recently focused on the new HF (high fluidity) alloy and also the further development of creep properties data for Alloy 5. Room temperature ageing and creep results have been extended for the HF alloy. The effect on Alloy 5 casting section thickness on creep properties is under current investigation; available data and analysis are described. The new results will be put in the perspective of other zinc alloy data and include a scientific basis of explanation of the observed results.

3. Introduction:

Recent research in zinc alloys has concentrated on developing both creep-resistant compositions for high-temperature service and high-fluidity compositions for ultra-thin die casting. The Zamak alloy family (Alloys 2, 3, 5, 7) offers an attractive combination of properties but is limited by creep at higher temperatures. Past research has sought to improve creep resistance by increasing aluminum content (ZA alloys) or through microalloying. The ACuZinc alloys identified Al and Cu as key elements for improving creep resistance. Alloy 7, a low-Mg version of Alloy 3, offers increased fluidity. This concept was extended to the HF (high fluidity) alloy, which has a higher Al content and low Mg content, showing noticeable improvements in fluidity. This paper investigates the creep and ageing behaviors of several of these alloys, including the new HF alloy, to provide a scientific basis for their performance.

4. Summary of the study:

Background of the research topic:

The application of zinc die casting alloys at elevated temperatures or under constant load is limited by their creep properties. Furthermore, the development of high-fluidity alloys for thin-wall applications necessitates a thorough understanding of their mechanical behavior, including creep and the effects of ageing over time.

Status of previous research:

Previous work led to the development of various zinc alloy families, including Zamak, ZA, ACuZinc, and EZAC®, each with specific improvements in properties like creep resistance or fluidity. Research has identified that increasing Al and Cu content improves creep resistance, while lowering Mg and increasing Al content improves fluidity. However, a comprehensive, comparative study on the interaction between ageing phenomena and creep behavior across standard, high-creep, and high-fluidity alloys was needed.

Purpose of the study:

The study aimed to investigate and quantify the creep and ageing behaviors of five prominent zinc die casting alloys: Alloy 3, Alloy 5, Alloy 2, ZA-8, and the new HF alloy. The objective was to analyze the effects of alloy composition, casting section thickness, testing temperature, and artificial ageing on creep properties and to provide a scientific explanation for the observed results.

Core study:

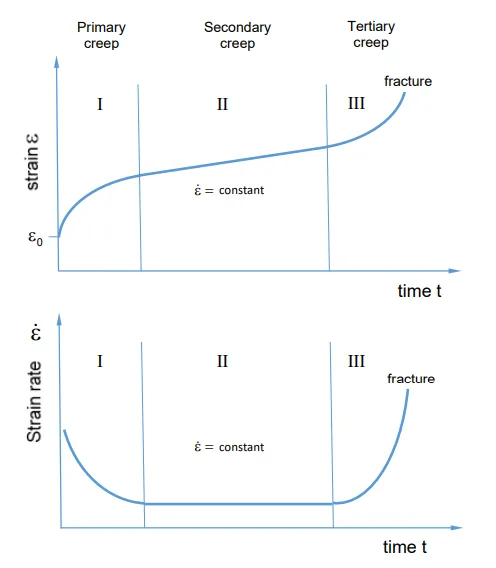

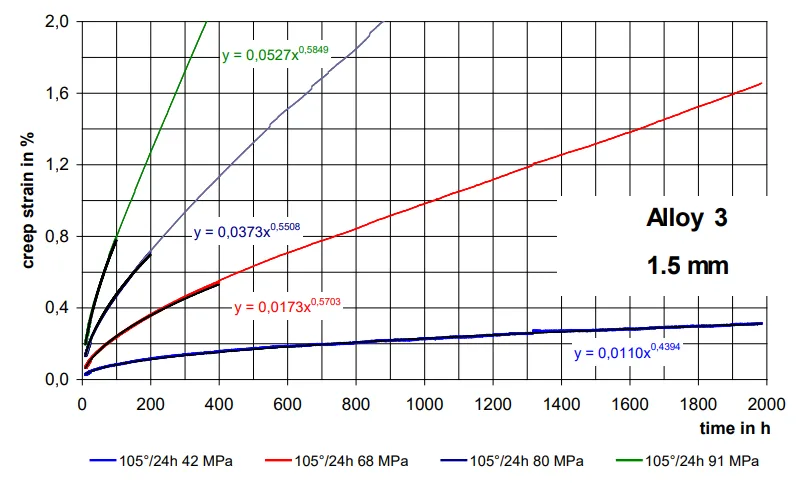

The core of the study involved conducting a series of long-term creep tests on the five selected alloys. The tests were performed under various constant stress levels at both room temperature and +85°C. The influence of microstructure was examined by using specimens with different wall thicknesses (1.5 mm and 3.0 mm) and by comparing as-cast samples to samples that underwent artificial ageing at 105°C for extended durations. The resulting data was mathematically modeled to describe the primary and secondary creep stages.

5. Research Methodology

Research Design:

The study employed an experimental research design to measure and compare the time-dependent plastic deformation (creep) of different zinc alloys under controlled conditions. The design systematically varied key parameters including alloy composition, applied stress, temperature, specimen thickness, and ageing condition to isolate and understand their respective influences on creep behavior.

Data Collection and Analysis Methods:

Data was collected by measuring the strain (elongation) of test specimens as a function of time under a constant tensile load. The primary creep stage was mathematically described using a power function (ε = c·t^a), while the secondary stage was analyzed in the context of Norton's Law (έs = A(σ/G)^n·e^(-Q/RT)). The stress exponent 'n' was calculated from the slopes of creep rate vs. stress plots on a log-log scale.

Research Topics and Scope:

The research focused on the primary and secondary creep stages of five zinc die casting alloys: 3, 5, 2, ZA-8, and HF. The scope included the effects of:

- Alloy composition (specifically Al and Cu content).

- Applied stress (40-100 MPa at RT; 12-50 MPa at 85°C).

- Testing temperature (Room Temperature and 85°C).

- Artificial ageing (at 105°C for up to 1000 hours).

- Casting wall thickness (1.5 mm and 3.0 mm).

The study did not extend to the tertiary creep stage or fracture.

6. Key Results:

Key Results:

- The primary creep behavior of all tested alloys can be described by a power law function, ε = c·t^a. The secondary creep behavior is consistent with Norton's power-law creep equation.

- Creep resistance is strongly influenced by copper content. Alloy 2 (2.95% Cu) exhibits the lowest creep rate, followed by Alloy 5 (0.85% Cu), ZA-8, and finally Alloy 3 and the HF alloy, which have the highest creep rates (Figure 17).

- Increasing the testing temperature from room temperature to 85°C increases the creep rate by a factor of approximately 700, corresponding to an activation energy for self-diffusion of zinc of about 94 kJ/mol (Figure 13).

- Prolonged artificial ageing significantly increases the creep rate. For Alloy 5, ageing at 105°C for 1000 hours resulted in a creep rate nearly 50 times higher than that of samples aged for 24 hours (Figure 15). This is attributed to the depletion of alloying elements from the primary zinc phase.

- Increased wall thickness reduces the creep rate. For Alloy 5, a 3.0 mm thick specimen showed lower creep strain compared to a 1.5 mm specimen under the same stress, due to a coarser microstructure (Figure 16).

- The stress exponent 'n' for the alloys at room temperature was determined to be between 5.7 and 7.6, confirming that the dominant mechanism is power-law creep (Table 3).

Figure Name List:

- Figure 1: Ragone fluidity distances of Alloy 7, HF and Superloy, cast at 435°C

- Figure 2- Primary (left) and eutectic phase (right) in Alloy 5 dark: Al-rich, bright: Zn-rich [8]

- Figure 3- Typical creep curve of Zn-alloys

- Figure 4- Creep rates from all measured alloys calculated utilizing equation 3

- Figure 5- Room temperature creep behavior for Alloy 3 after artificial ageing (105°C / 24 h)

- Figure 6- Creep behaviour for Alloy 3 after artificial ageing (105°C / 24 h), log-log scale

- Figure 7- Room temperature creep behavior for Alloy 5 after artificial ageing (105°C / 24 h)

- Figure 8- Room temperature creep behavior for Alloy 2 after artificial ageing (105°C / 24 h)

- Figure 9- Room temperature creep behavior for ZA8 naturally aged over 6 years after artificial ageing (105°C / 24h)

- Figure 10- Room temperature creep behavior for HF alloy as cast and artificially aged 3 days at 105°C

- Figure 11- Creep behavior Alloy 5 at elevated temperatures as cast and artificially aged 7 days at 95°C

- Figure 12- Creep elongation as a function of time and stress of Alloy 5 at +85°C

- Figure 13- Creep rate of Alloy 5 for two testing temperatures

- Figure 14- Stress exponent n for Alloys 2, 3 and 5, as a function of creep strain

- Figure 15- Room temperature creep rate versus ageing time as a function of wall thickness, Alloy 5

- Figure 16- Creep strain as a function of wall thickness, Alloy 5 artificially aged at 105°C / 24 h

- Figure 17- Creep rate with 60 MPa stress at room temperature and 1.5 mm wall thickness after 1% creep strain (artificially aged 24h/105°C, ZA8 with 6 years natural ageing)

- Figure 18- 2D creep deformation mechanism map for coarse pure Zinc, red frame means the region researched in the project [11]

![Figure 18- 2D creep deformation mechanism map for coarse pure Zinc, red frame means the region researched in the project [11]](https://castman.co.kr/wp-content/uploads/image-3299.webp)

7. Conclusion:

All tested zinc die-casting alloys exhibit a distinct primary creep stage characterized by a decreasing creep rate due to strain hardening, which can be mathematically expressed with a power law function (ε = c·t^a). The coefficient 'c' depends on stress, temperature, and microstructure, while the exponent 'a' is sensitive to temperature and alloy type. The secondary creep region follows Norton's equation, with a stress exponent 'n' mainly influenced by alloy type. The experimental results confirm that power-law creep is the dominant deformation mechanism under the tested conditions. For maximum creep resistance, a high-Cu content zinc alloy with a coarse microstructure (achieved through higher wall thickness and die temperature) is necessary. Notably, creep resistance is reduced by artificial ageing for more than one day at 100°C or higher.

8. References:

- F. Porter, Zinc Handbook: properties, processing, and use in design, Marcel Dekker, New York, NY, 1991.

- S.D. Galvez, PhD Thesis, University of Liege, Belgium, 1984.

- M.D. Rashid, M.S. Hanna, US Patent, (4,990,310), 1991.

- Benson, J.M., Hope, D., and Goodwin, F.E., "Development of a Creep Resistant Hot Chamber Die Casting Zinc Alloy," NADCA 2000 Conference, Nov. 6-7, 2000, Rosemont, IL

- Benson, J.M., Hope, D., Stander, C.M. and Goodwin, F.E., "Assessment of Experimental Near-Eutectic Zn-Al-Cu Casting Alloys", 23rd NADCA Congress, Chicago, IL, June 13-15, 2004.

- Anderson, E.A. and Werley, G.L., "The Effect of Variations in Aluminum Content on the Strength and Permanence of the A.S.T.M. No. XXIII Zinc Die-Casting Alloy", Proceedings of the American Society for Testing Materials, Philadelphia, PA, 1934.

- Friebel, V.R. and Roe, W.P., "Fluidity of Zinc-Aluminum Alloy", Modern Castings, September 1962, pp. 117-120.

- F.E. Goodwin, K. Zhang, A. Filc, N-Y Tang, R. Holland, W. Dalter and T. Jennings, "Progress and Development of Thin Section Die Casting Technology," Proceedings of 110th Metalcasting Conference, North American Die Casting Association, Columbus, OH, April 18-21, 2006.

- Rollez, D., Gilles, M., Erhard, N., "Ultra Thin Wall Zinc Die Castings", Die Casting Engineer, March 2003, pp32-35

- J.M. Gobien, “Creep Properties of Zinc-Aluminum casting alloys a function of grain size, Ph.D. thesis, North Carolina State Univ., 2010, summarized in J.M. Gobien, R.O. Scattergood, F.E. Goodwin, C.C. Koch, "Mechanical Behavior of Bulk Ultra-fine-grained Zn-Al die-Casting Alloys,” Materials Science and Engineering, 2009, Vol. 518, No. 1-2, pp. 84-88.

- H.J. Frost, M.F. Ashby, Deformation Mechanism Maps: The Plasticity and Creep of Metals and Ceramics, Pergamon, Oxford, U.K., 1982.

- F. E. Goodwin, L. H. Kallien, W. Leis, "New Mechanical Properties Data for Zinc Casting Alloys, Proceedings NADCA 2014 Die Casting Congress, Milwaukee, WI, USA, pps. T14-032.

- Cyril Stanley Smith, “Al-Cu-Zn“ in “Constitution of Ternary Alloys, Metals Handbook, 1948 edition, p. 1244

Expert Q&A: Your Top Questions Answered

Q1: Why does prolonged ageing increase the creep rate when it is known to stabilize short-term tensile properties?

A1: The paper explains on page 10 that this counter-intuitive effect is due to microstructural changes. During prolonged ageing, strengthening alloying elements like Al and Cu diffuse out of the primary zinc phase. This process leads to the formation of a separate Cu-rich epsilon phase and reduces the Zn grain size, both of which contribute to higher creep rates by making diffusion and grain boundary sliding easier.

Q2: What is the primary creep mechanism observed in these zinc alloys under the tested conditions?

A2: The results strongly indicate that power-law creep is the dominant mechanism. This is supported by the calculated stress exponent 'n' from Norton's Law, which falls between 5.7 and 7.6 for the alloys at room temperature (Table 3). This range is characteristic of creep controlled by dislocation climb, which is a type of power-law creep, as shown in the deformation map in Figure 18.

Q3: The paper mentions a new HF (high fluidity) alloy. How does its creep performance compare to standard Zamak alloys?

A3: According to the data presented in Figure 17, the HF alloy exhibits a high creep rate, comparable to that of the copper-free Alloy 3. While its high fluidity is advantageous for casting ultra-thin sections, its poor creep resistance makes it less suitable for applications that will be under a sustained load, especially when compared to copper-bearing alloys like Alloy 5 and Alloy 2.

Q4: How significant is the effect of temperature on the creep rate of these zinc alloys?

A4: The effect is extremely significant. The paper states on page 8 and illustrates in Figure 13 that the creep rate increases by a factor of approximately 700 when the temperature is raised from 25°C to 85°C. This is based on an activation energy (Q) of 94 kJ/mol, which corresponds to the energy required for self-diffusion in zinc, highlighting that creep is a thermally activated process.

Q5: Does casting wall thickness affect creep behavior, and if so, why?

A5: Yes, a greater wall thickness reduces the creep rate, as shown for Alloy 5 in Figure 16. The paper explains on page 10 that this is because thicker sections cool more slowly, resulting in a larger grain size. A coarser microstructure with a lower volume fraction of grain boundaries is more resistant to creep mechanisms like grain boundary sliding, thus improving the overall creep performance of the component.

Q6: The paper uses a power law function (ε = c·t^a) to describe primary creep. What do the coefficients 'c' and 'a' represent in practical terms?

A6: As described on page 11, the coefficient "c" represents the initial magnitude of creep and is dependent on external conditions like stress and temperature, as well as internal factors like microstructure and alloy type. The exponent "a" describes how quickly the creep rate decreases over time due to strain hardening. A lower value of 'a' means the material strain hardens more effectively, leading to a more rapid decrease in the initial high creep rate.

Conclusion: Paving the Way for Higher Quality and Productivity

The challenge of designing reliable zinc components under load requires a deep understanding of Zinc Die Casting Creep and its interaction with material ageing. This research provides a critical breakthrough by quantifying how alloy composition (especially copper), temperature, wall thickness, and thermal history collectively dictate long-term performance. The discovery that prolonged ageing can severely degrade creep resistance is a vital insight for engineers aiming to predict component lifetime accurately.

At CASTMAN, we are committed to applying the latest industry research to help our customers achieve higher productivity and quality. If the challenges discussed in this paper align with your operational goals, contact our engineering team to explore how these principles can be implemented in your components.

Copyright Information

This content is a summary and analysis based on the paper "Interaction of Creep and Ageing Behaviors in Zinc Die Castings" by "F. E. Goodwin, L. H. Kallien, W. Leis".

Source: This paper was presented at the 2016 Die Casting Congress & Tabletop, hosted by the North American Die Casting Association (NADCA).

This material is for informational purposes only. Unauthorized commercial use is prohibited.

Copyright © 2025 CASTMAN. All rights reserved.