This article introduces the paper 'Life Cycle Environmental Impact of Magnesium Automotive Components' published by 'TMS (The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society)'.

1. Overview:

- Title: Life Cycle Environmental Impact of Magnesium Automotive Components

- Author: P. Koltun, A. Tharumarajah and S. Ramakrishnan

- Publication Year: January 2016

- Publishing Journal/Academic Society: TMS (The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society)

- Keywords: Magnesium production, Electrolytic magnesium, Lifecycle analysis, Greenhouse impact, Converter housing

2. Abstracts or Introduction

The development of magnesium applications in the automotive sector is gaining considerable traction. A critical aspect of this growing interest is the evaluation of the environmental footprint of magnesium components from cradle to grave. To comprehensively address this concern, a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is essential. This paper presents such an assessment focusing on a specific automotive component: the converter housing (CH). The study meticulously examines the environmental impact, commencing from the production of magnesium ingots through manufacturing, assembly, vehicle utilization, and end-of-life recycling. A comprehensive sensitivity analysis is performed to evaluate the influence of key process variables on the environmental performance of the magnesium component. These parameters include alternative cover gases to SF6, enhancements in product yield, and the incorporation of secondary magnesium. Based on this analysis, various environmental performance scenarios are proposed to benchmark the environmental impact of magnesium components against functionally similar components made from magnesium produced in China, aluminum, and iron. The investigations reveal the potential for significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions through the implementation of lighter magnesium components. Furthermore, process optimizations aimed at impact reduction can shorten the break-even distances in vehicle usage, at which point magnesium becomes environmentally competitive with alternative metals.

3. Research Background:

Background of the Research Topic:

The increasing environmental consciousness in the automotive industry is driving the adoption of lightweight magnesium components to reduce vehicle emissions. This trend necessitates a thorough understanding of the environmental impacts associated with the magnesium value chain. The paper focuses on the greenhouse impact related to the manufacturing, use, and recycling of magnesium automotive components, aiming to address and improve the environmental performance of this value chain.

Status of Existing Research:

Prior research has primarily focused on quantifying the greenhouse impact of magnesium metal production via electrolytic processes. However, the environmental implications of component manufacturing, and the benefits derived from employing magnesium components in automobiles, have not been extensively explored. This paper aims to bridge this gap by extending the life cycle boundary from "cradle-to-grave," encompassing manufacturing, use, and recycling stages.

Necessity of the Research:

To gain a holistic understanding of the environmental impact of magnesium automotive components, it is crucial to move beyond the magnesium production phase and analyze the complete life cycle. This research is necessary to identify critical stages and parameters influencing the environmental performance and to explore improvement opportunities across the entire value chain, thereby facilitating informed decisions regarding material selection in automotive design.

4. Research Purpose and Research Questions:

Research Purpose:

The primary objective of this LCA study is to evaluate different processes, materials, and systems that significantly contribute to the environmental impact throughout the life cycle of magnesium automotive components. A further goal is to pinpoint potential improvements aimed at minimizing these impacts. The study specifically focuses on global warming impact, quantified by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the product system.

Key Research:

The key research question is to quantify and analyze the cradle-to-grave GHG emissions associated with a magnesium converter housing (CH) used in automobiles. This includes:

- Assessing the GHG emissions at each stage of the life cycle: primary magnesium production, component manufacturing, vehicle assembly, vehicle use, and secondary magnesium production (recycling).

- Conducting sensitivity analysis to identify key parameters influencing GHG emissions, such as cover gas type (SF6 vs. AM-Cover), product yield in manufacturing, and secondary magnesium content.

- Comparing the GHG emissions of magnesium CH with functionally equivalent components made from iron and aluminum.

Research Hypotheses:

The study implicitly hypothesizes that:

- Lightweighting through magnesium components will lead to a reduction in GHG emissions during the vehicle use phase, potentially offsetting higher emissions in the production phase.

- Process improvements, such as using alternative cover gases and increasing product yield, can significantly reduce the GHG footprint of magnesium components.

- Increasing the utilization of secondary magnesium will lower the overall environmental impact.

5. Research Methodology

Research Design:

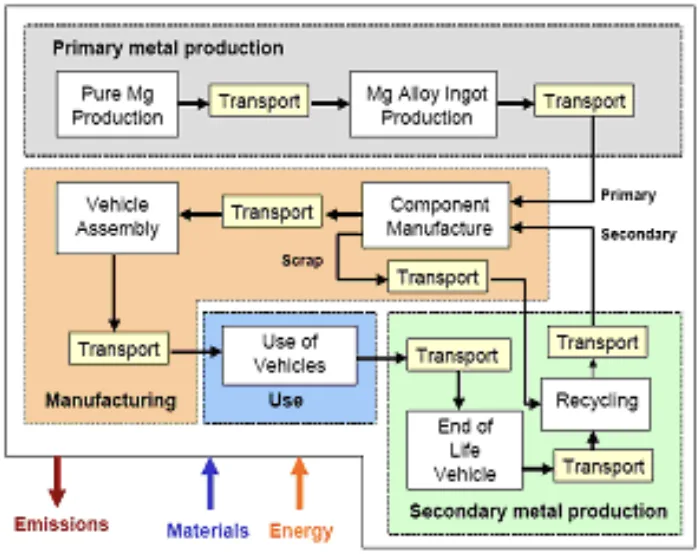

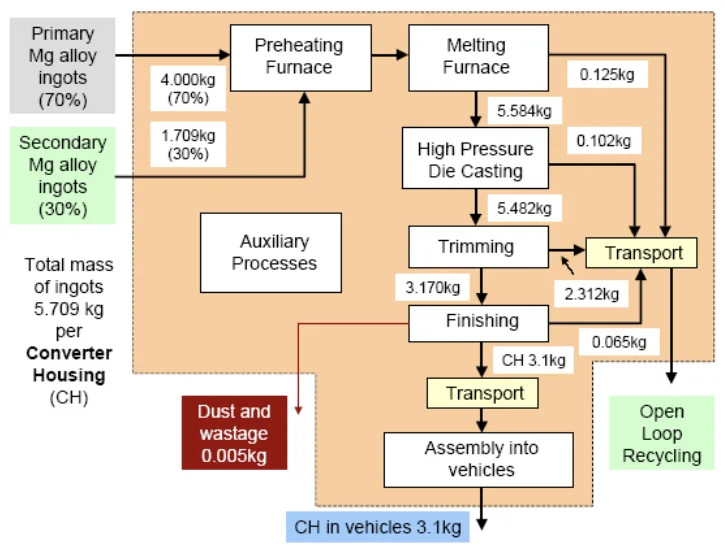

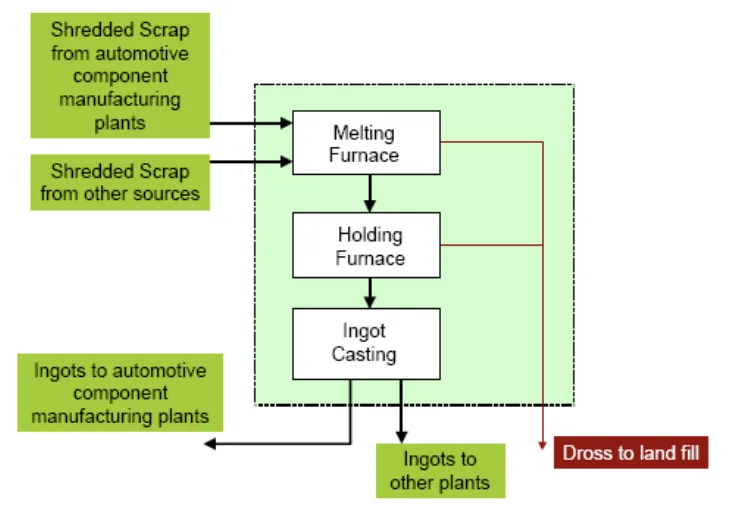

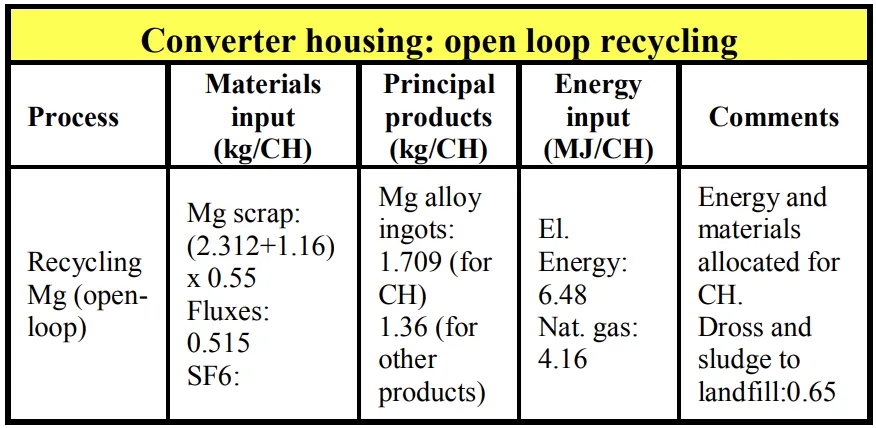

The research employs a cradle-to-grave Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology, adhering to international standards. The system boundary encompasses four life cycle stages: primary magnesium production, manufacturing and assembly, vehicle use, and secondary magnesium production via open-loop recycling (Figure 2). A generic product system approach is adopted, representing a collection of unit processes within each life cycle stage.

Data Collection Method:

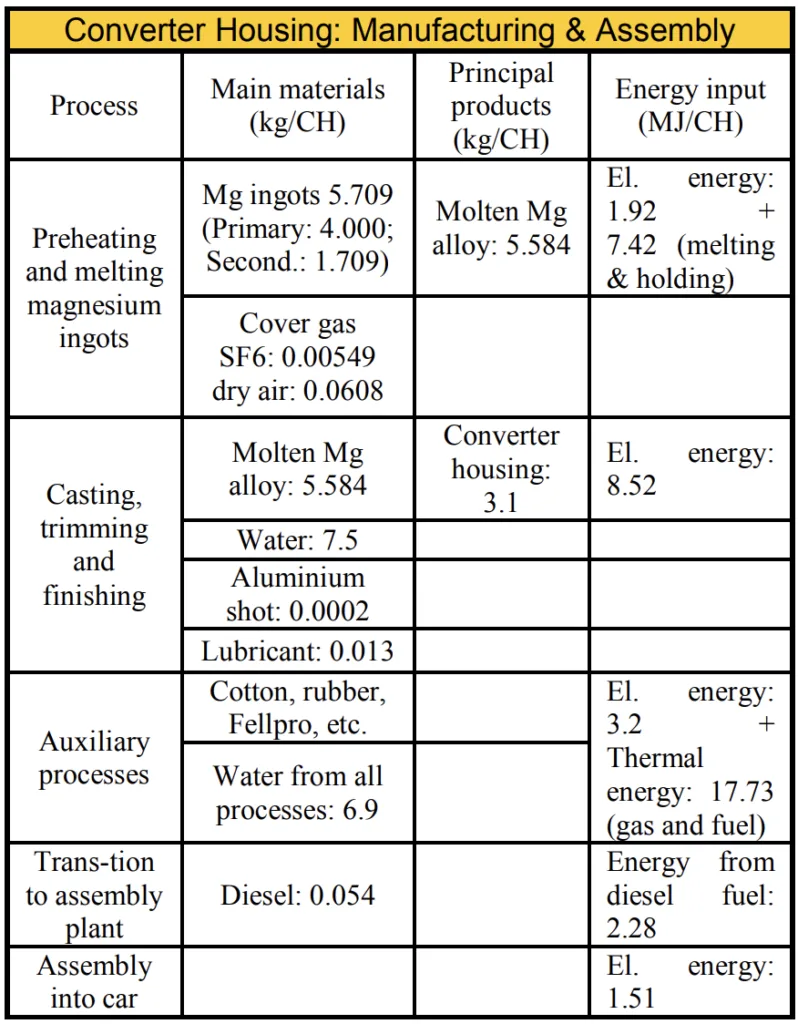

Primary data for magnesium production (electrolytic process using AMC proprietary technologies in Australia) and manufacturing processes (HPDC in USA) were utilized. Data for auxiliary materials and energy consumption were derived from industry data and databases like SimaPro and ecoinvent. Specific data sources include:

- Mass of magnesium converter housing: 3.1kg (obtained from [4]).

- Secondary magnesium content in manufacturing: 30% (assumed based on [7]).

- Electrical energy emission factor for USA: 0.207 kg CO-eq/MJ [8, 9].

- SF6 cover gas consumption: 0.96g per 1kg molten metal [9].

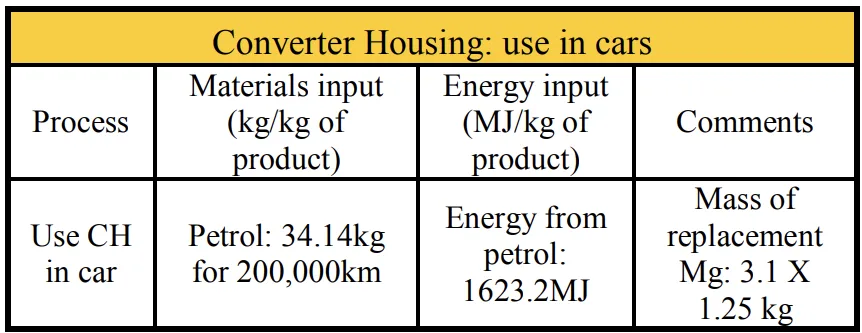

- Vehicle parameters: mid-size car (1400kg), fuel consumption (8.5 litres/100km) [10], vehicle lifetime (200,000km).

- GHG emission factor for gasoline: 2.85 kg CO2-eq/litre [10].

Analysis Method:

The LCA model was developed and analyzed using SimaPro LCA software [11]. Global Warming Potential (GWP) was selected as the impact category, and GHG emissions were quantified in kg CO2-eq per functional unit (converter housing). Sensitivity analyses were conducted by varying key parameters to assess their influence on the overall GHG impact. Comparative analyses were performed against alternative materials (aluminum and iron) and different production scenarios (e.g., Chinese magnesium production, different cover gases).

Research Subjects and Scope:

The subject of the LCA is a magnesium converter housing (CH) made from AZ91 alloy, a representative automotive component used in cars with automatic transmissions (Figure 1). The functional unit is defined as "the product itself, i.e. CH." The study focuses on the global warming impact and is geographically scoped to production in Australia and USA, and vehicle use in the USA. The analysis considers magnesium produced via electrolytic process and secondary magnesium production in the USA.

6. Main Research Results:

Key Research Results:

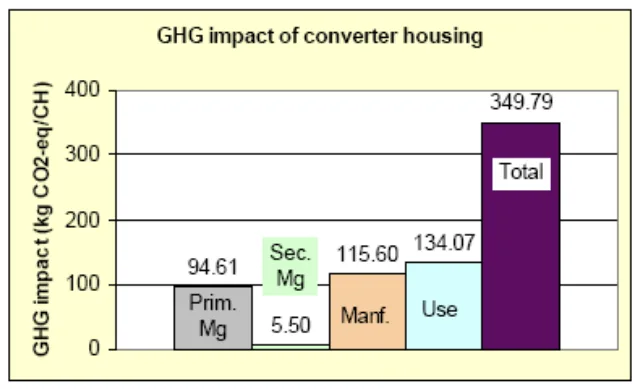

- The cradle-to-grave GHG impact of the magnesium converter housing (CH) under nominal conditions is 349.8 kg CO2-eq/CH (Figure 5).

- Primary magnesium production (Prim. Mg), vehicle use (Use), and manufacturing (Manf.) are the most significant contributors to the total GHG impact (Figure 5).

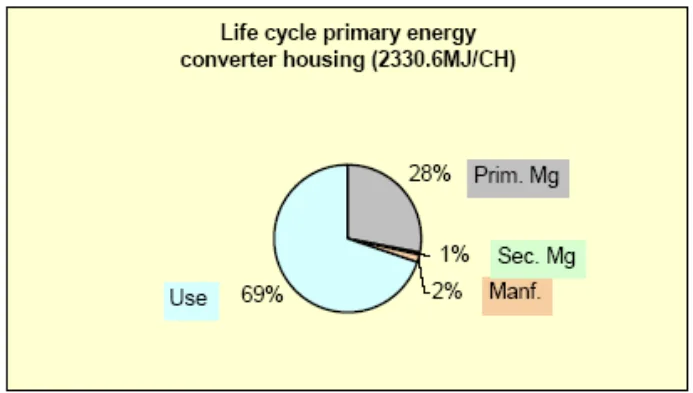

- Primary energy consumption over the life cycle is 2330.6 MJ/CH, with primary magnesium production and vehicle use being the major contributors (Figure 6).

- Using SF6 as a cover gas in manufacturing and recycling significantly elevates the GHG impact due to its high GWP (22,200).

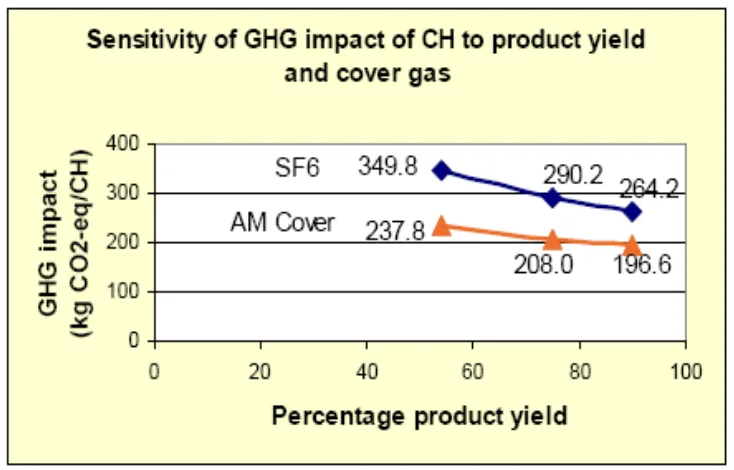

- Substituting SF6 with AM-Cover gas (containing HFC-134a, GWP: 1,600) substantially reduces the GHG impact (Figure 7 and 8).

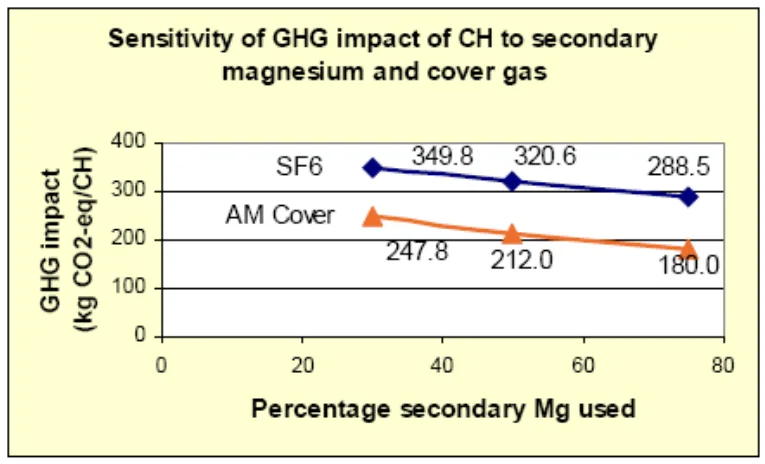

- Increasing product yield in die casting and the proportion of secondary magnesium also leads to notable reductions in GHG emissions (Figure 7 and 8).

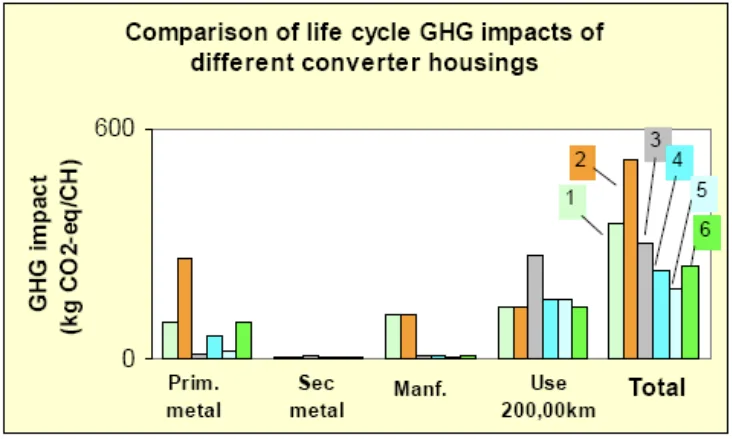

- Compared to a converter housing made from Chinese magnesium (using SF6 throughout), the nominal system (Australian Mg, SF6) has a lower GHG impact, but both are significantly higher than systems using AM-Cover gas or aluminum (Figure 9).

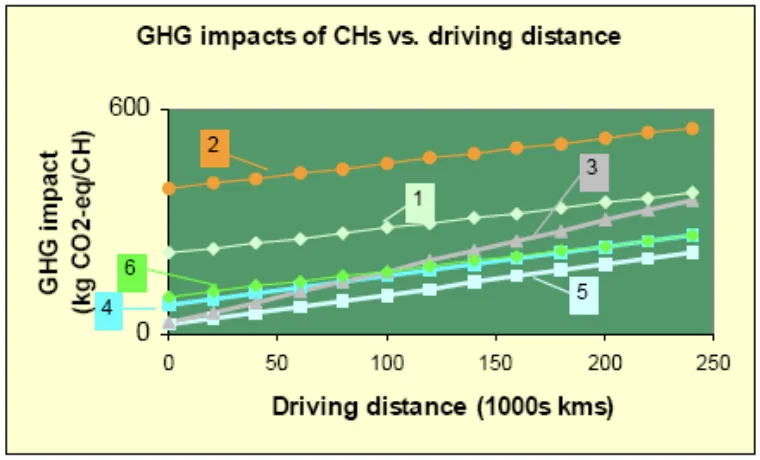

- Magnesium CH becomes GHG-competitive with iron CH at a driving distance of approximately 100,000 km when AM-Cover gas is used (Figure 10).

Analysis of presented data:

The data clearly indicates that the use phase dominates the GHG emissions for automotive components. Lightweighting with magnesium offers substantial potential for reducing these use-phase emissions. However, the production and manufacturing phases, particularly the use of SF6 cover gas, contribute significantly to the overall footprint. Sensitivity analyses highlight the effectiveness of process improvements, especially cover gas substitution and increased recycling, in mitigating the environmental impact of magnesium components. The comparative analysis underscores the importance of considering the entire life cycle and production scenario when evaluating the environmental benefits of material choices.

Figure Name List:

- Figure 1. Converter housing (CH)

- Figure 2. Generic product system considered for LCA study

- Figure 3. Manufacturing and assembly of CH

- Figure 4 Open loop recycle of magnesium scrap for secondary metal production

- Figure 5. GHG impact of CH over the life cycle.

- Figure 6. Primary energy consumption of CH over the life cycle

- Figure 7. Sensitivity of GHG impact of CH to product yield and the cover gas used in manufacturing and recycling

- Figure 8. Sensitivity of GHG impact of CH to product percentage of secondary magnesium and the cover gas used in manufacturing and recycling

- Figure 9. Comparison of GHG impact of different materials product systems

- Figure 10. GHG impact of different product system for CH vs. driving distance

7. Conclusion:

Summary of Key Findings:

This LCA study on magnesium converter housings reveals that while the use phase is the largest contributor to GHG emissions, significant reductions can be achieved through lightweighting with magnesium. However, the choice of cover gas (SF6 vs. AM-Cover) in manufacturing and recycling, product yield in die casting, and the utilization of secondary magnesium are critical factors influencing the overall environmental performance. Substituting SF6 with AM-Cover gas, increasing recycling rates, and improving product yield are effective strategies for reducing the GHG footprint of magnesium automotive components.

Academic Significance of the Study:

This study provides a comprehensive cradle-to-grave LCA of magnesium automotive components, extending beyond previous research that primarily focused on magnesium production. It offers valuable insights into the environmental hotspots within the magnesium component life cycle and quantifies the impact of key process parameters. The comparative analysis with alternative materials and production scenarios contributes to a deeper understanding of the environmental implications of material choices in automotive engineering.

Practical Implications:

The findings have direct practical implications for the die casting industry and automotive manufacturers:

- Emphasize the importance of adopting alternative cover gases like AM-Cover to replace SF6 in magnesium processing to significantly reduce GHG emissions.

- Highlight the need to improve product yield in HPDC processes to minimize scrap generation and associated environmental burdens.

- Promote the increased use of secondary magnesium in component manufacturing to reduce reliance on primary magnesium production.

- Provide data to support informed material selection decisions in automotive design, considering the life cycle environmental impacts.

Limitations of the Study and Areas for Future Research:

This study primarily focuses on Global Warming Potential (GWP). Future research should expand the scope to include other relevant environmental impact categories, such as resource depletion, acidification, and eutrophication, for a more holistic environmental assessment. Furthermore, the study is geographically focused on specific regions (Australia, USA, China). LCAs considering regional variations in energy grids, transportation distances, and recycling infrastructure would enhance the generalizability of the findings. Further investigation into closed-loop recycling systems for magnesium and the environmental impacts of non-metallic automotive components are also recommended.

8. References:

- [1] Brown R.E., "Magnesium industry growth in the 1990 period," Magnesium Technology 2000, ed. H.I. Kaplan, J.N. Hryn and B.B. Clow (Warrendale, PA: The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society, (2000), 3-12.

- [2] Albright, D.L. and Haagensen, J.O. Life cycle inventory of magnesium, in Proceedings International Magnesium Association 54, Toronto, Canada, (1997) pp. 32-37.

- [3] AS/NZS ISO 14000: Australia/New Zealand Standard Environmental management - life cycle assessment principles and framework, Standards Australia, Australia, (1998) p. 12.

- [4] Beggs P., Brynes D., Song G., Qian M., Song W., Christodoulou P., Brandt M.: Design and Development of Magnesium Alloys, BTRA/CAST Joint Project Phase 1 - Project Review Report, CAST Report Number: CASTREP/2000135, (2000)

- [5] Stanley R. W., Berube M., Celik C., Oosaka Y., Pearcy J., and Avedesian M. "The Magnola process for magnesium production," Proceedings of the International Magnesium Association 54: Magnesium Trends, (1997), 58-65.

- [6] .Ramakrishnan S, Koltun P. "Comparison of the Greenhouse Impacts of Magnesium Produced by Electrolytic and Pidgeon Processes". TMS (The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society), (2004).

- [7] Kramer D. A. "Magnesium Recycling in the United States in 1998" U.S. Geological Survey, Circular 1196-E, http://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/c1196e (Online Only).

- [8] Dorsam H., Westofen S. "Magnesium Melting, Casting and Remelting in Foundries", Magnesium Technology, (2002) p. 725-737

- [9] Amersfoort B.V., SimaPro Database, Pre Consultants, The Netherlands, (2003).

- [10] Moore D.M. "Environment and Life Cycle Benefit of Automotive Aluminium" Canadian Technology Development, http://www.alcan.com, Toronto, Canada, Oct., (2001).

- [11] Antrekowitsch H., Hanko G. "Recyclin of Different Type of Magnesium Scrap", Magnesium Technology, TMS, The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society, (2002)

- [12] http://www.rauch-ft.com/e001home.htm: Magnesium machine furnace MMO and MMOSL., (2003).

- [13] International Primary Aluminum Institute, "Aluminium Applications and Society Life Cycle Inventory of the World Wide Aluminium Industry with Regard to Energy Consumption and Emissions of Greenhouse Gases", Report 1 Automotive, May (2000).

- [14] Gjestland H., Magers D. "Practical Usage of Sulphur Hexafluoride for Melt Protection in the Magnesium Die-Casting Industry", Norsk Hydro, Magnesium Technology (2001).

9. Copyright:

- This material is "Paul Koltun, A. Tharumarajah and S. Ramakrishnan"'s paper: Based on "Life Cycle Environmental Impact of Magnesium Automotive Components".

- Paper Source: DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-48099-2_29

This material was summarized based on the above paper, and unauthorized use for commercial purposes is prohibited.

Copyright © 2025 CASTMAN. All rights reserved.